Celebrating the accession of the city of Differdange to the CIPU convention, we interviewed Laura Pregno, alderwoman for urban development and Manuel Lopes Costa, chief planner for the City of Differdange. Differdange is the third-largest city in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. The interview covered climate change adaptation and climate action in Luxembourg urban areas.

Interviewer: Measures addressing climate change can reduce hazardous emissions, or deal with the consequences of climate change. What role does local development play in adapting to climate change?

Alderwoman Pregno and chief planner Lopes Costa: Urban development is important to climate change adaptation with municipal measures aligned to broader objectives. The city of Differdange directly contributes to Sustainable Development Goal 11 ‘Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ through a municipal guideline.

The 2018 guideline lays out principles and objectives for renovation and construction of public buildings in Differdange (available here in German). It directly refers to the Sustainable Development Goals, linking municipality measures to global climate change adaptation and climate action. When implementing local measures, it is important to consider these overarching objectives and strategies as this ensures that players at all levels are working towards the same objectives creating synergies and avoiding conflicts.

Linking municipal efforts to broader global policies still leaves municipalities free to adapt their own visions, strategies and objectives. We develop our own visions and strategies for climate change adaptation and climate action through urban and district development in our city. Referring to the global objectives helps us to use monitoring, with measurable effects that are visible for Differdange residents.

Differdange uses municipal planning to involve citizens, associations, public institutions and services as well as businesses. In addition, our starting point for climate change adaptation differs from other places. In Differdange we have different pre-requisites than elsewhere, calling for territorially integrated actions and measures. Urban and district development instruments help us to incorporate local specificities in policy making.

Interviewer: Where do you see priorities and opportunities to use existing or new spatial planning and urban development instruments for climate change adaptation in Luxembourg?

Alderwoman Pregno and chief planner Lopes Costa: Luxemburg municipalities already have a range of instruments to hand that enable climate change adaptation and climate action to be integral in urban development. From our point of view, these instruments are sufficient for such measures.

However, climate change adaptation and climate action often lack clearly defined objectives and measures at municipal level in Luxembourg. In Differdange and other municipalities instruments could not be used to their full potential to carry out projects as there were unclear overarching objectives. These ambiguities have their origin in political disputes or a lack of climate-related strategies at municipal level.

This is why we, the city of Differdange, are working on clear politically approved objectives. An urban strategy is currently under development which will align all urban development projects in Differdange to contribute to climate change adaptation and climate action. The strategy will complement the existing guideline and is being developed jointly with citizens and across political parties, ensuring that all parties will work on its implementation.

Once these clear and politically approved objectives are defined at local level, we can use urban development and planning to their full potential to implement concrete measures. Our strategy will ensure that climate change adaptation and climate action objectives are addressed in urban development. The local zoning plan, PAG (Plan d’aménagement general) will influence land-use in favour of climate change adaptation, with specific land-use plans (Plan d’aménagement particulier)and urbanistic concepts for vacant land (Schémas Directeurs) enabling measures for private or public development projects, such as building layout and even construction materials.

Interviewer: What role should climate change adaptation play in a sustainable urban development?

Alderwoman Pregno and chief planner Lopes Costa: In Luxembourg, impacts of climate change have become more visible in recent years. More frequent torrential rains, droughts and hazardous events have put climate change back into the population’s awareness. The most important instrument we as the city of Differdange have to counter these changes is sustainable urban development. Changing our urban landscape and making it more fit for the future will guarantee that our city remains liveable. Nevertheless, to make sure that we are all moving into the same direction we need joint visions and strategies. With our climate strategy, we increase leverage of our measures as we commit all political parties to shared objectives and measures.

Interviewer: Can converting urban brownfields help climate change adaption?

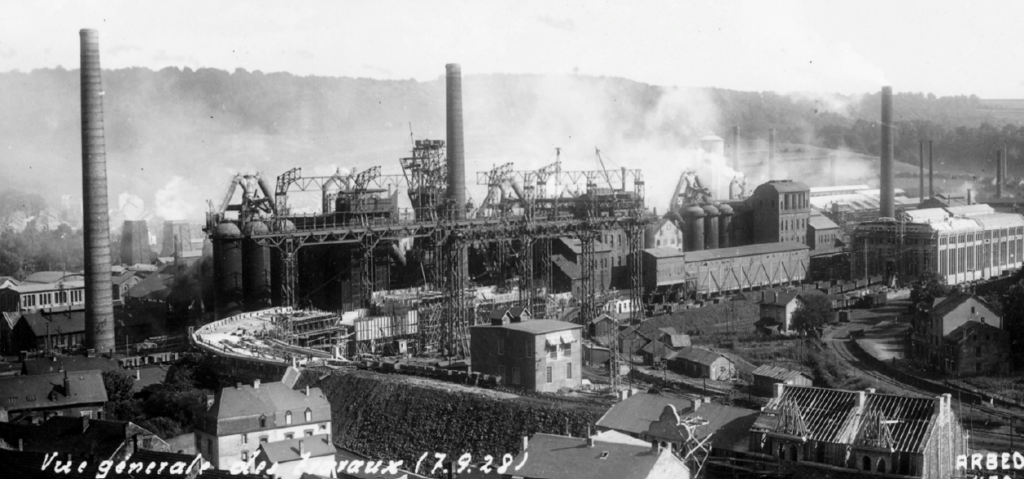

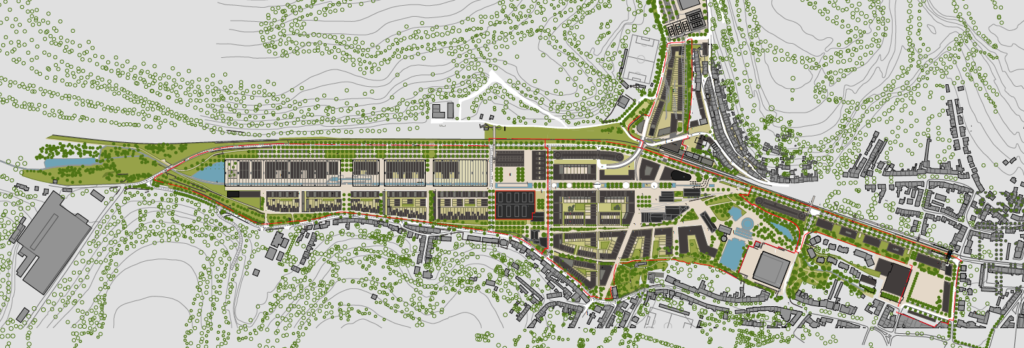

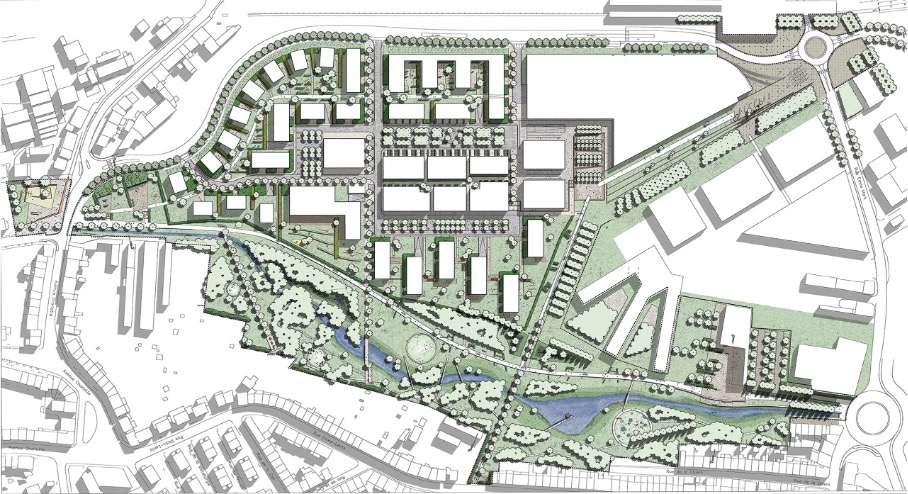

Alderwoman Pregno and chief planner Lopes Costa: We have brownfield conversion experience with the large development project ‘Plateau fu Funiculaire’ in the centre of Differdange. Since 2004, we have been developing this district together with many stakeholders. The brownfield was a former dumpsite for the nearby blast furnace and was developed in a way that connects the city districts of Differdange, Differdange, Oberkorn and Fousbann. We also re-naturalised the river Chiers with special attention on providing natural flooding surfaces.

This large-scale brownfield development has much more freedom compared to developments in existing urban areas. We discussed and balanced measures before they were realised in detail. This has helped to avoid conflicts. Also, planners optimally balance the three pillars of sustainable development; economy, ecology and society at project level.

However, this process takes time. It is important that concerns on climate change adaptation and climate action are considered in the planning process from the very beginning. Only then can the different needs and requirements be balanced through iterative discussions and negotiations between sector experts, so operational concepts can be developed and implemented.

In addition, brownfield development projects such as ‘Plateau du Funiculaire’ serve as testbeds for new approaches and technologies. Its size meant we faced challenges that could not be solved with existing planning approaches. An example is providing heat to the 600 units in the district. The area was planned with a centralised district heat system as early as 2007 to reduce infrastructure costs and to save energy. The idea could only be adopted later, but time is available in such large-scale brownfield developments.

Interviewer: Thank you and we will definitely cover the ‘Plateau du Funiculaire’ project in our upcoming descriptions of good practices from Luxembourg. What is the role of the CIPU for climate change adaptation in Luxembourg?

Alderwoman Pregno and chief planner Lopes Costa: The National Information Unit for Urban Policy (CIPU) is a platform to liaise partners and other players in Luxembourg on climate change adaptation. In addition to our measures in Differdange, all cities and municipalities across Luxembourg develop and implement climate change adaptation and climate action measures. CIPU events, workshops and related activities help bring this knowledge and experience together to create new knowledge. CIPU also facilitates discussion on difficulties encountered when implementing measures to support climate change adaptation and climate action. Critical reflection in the framework of CIPU events is crucial to designing and implementing changes to improve urban development in the country.

For any questions on the article, please refer to the author: sebastian.hans@spatialforesight.eu