Mondercange is the gateway to the former mining district in the industrial south of the country. As other municialities in Luxembourg, Mondercange has relatively high costs for living. The municipality has identified and implemented a special way of developing affordable housing for its residents.

Rationale for action

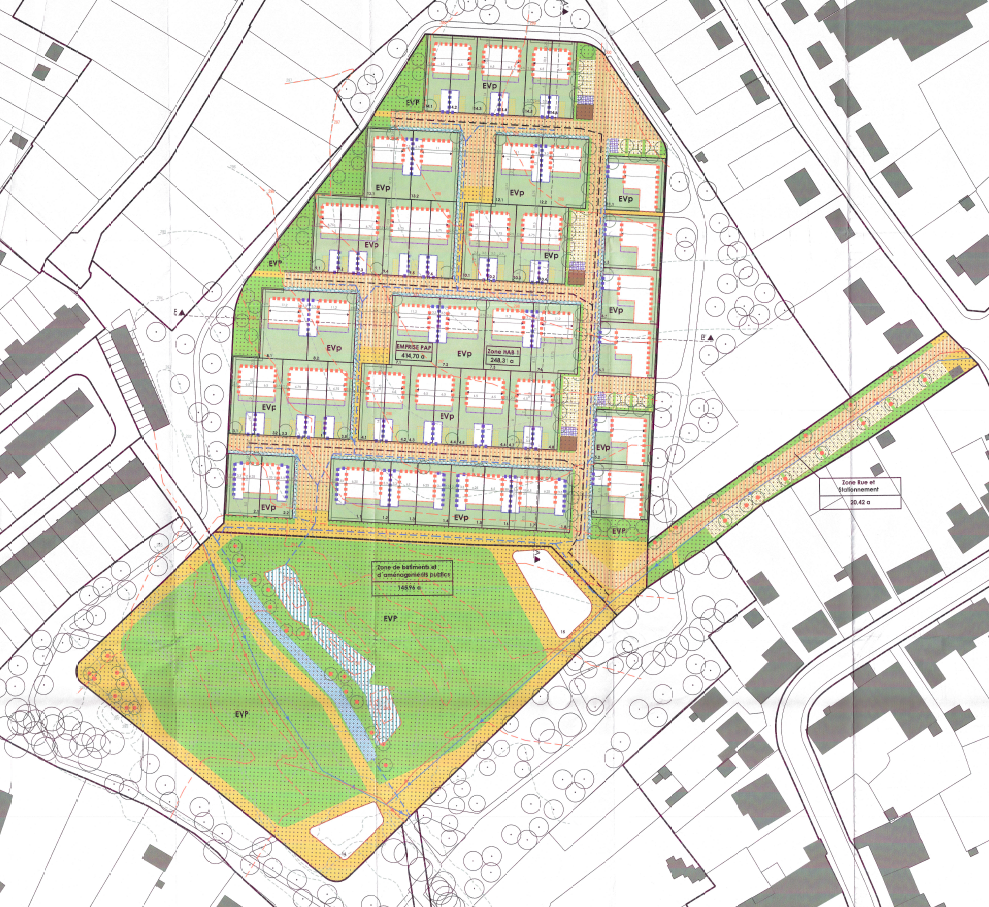

Mondercange lies in the densely populated southern part of the country where there is high demand for housing, including high demand for affordable housing. To provide affordable housing for its residents, the municipality of Mondercange has targeted an unused area of 4.15 hectares for development within the town. The objective of this development project, called Molter, is to create a residential district dedicated to affordable housing including a large park.

Objective

In developing this area, the municipality has chosen a special way of creating housing. Issuing building permits in Luxembourg depends on lots being developed with a specific land-use plan (PAP). The PAP specifies aspects of construction, such as density, roof form, parking, etc. and follows provisions laid out in the general land-use plan (PAG), which is valid for the entire municipality. The normal procedure in Luxembourg is for a private developer to create the PAP by contracting an urban planner or an architect. The expert then ensures the public provisions and private plans for the site are compatible. For the Molter PAP, the municipal administration contracted an urban planner. He then planned the new district respecting the public provisions and translating the development concept from the municipality into a concrete development plan.

Time frame

The PAP were developed between 2011 and 2012. After their approval in 2013, construction started until the project was realised in 2017.

Key players

Key players are the municipal administration of Mondercange, urban planning bureaus and SNHBM (the national association for affordable housing).

Implementation steps and processes

The process started with defining criteria for the plot to decide on the future use of the area. The emphasis was put on affordable housing for specific population groups. The allocation of the housing units will depend on the applicant’s age, number of years lived in the municipality and children in the household. Additionally, the housing will be available for families that do not have property yet and that are eligible for a construction premium, as defined by the Ministry of Housing. So, the units are for people in real need of affordable housing. Once the criteria and conditions were established, the municipality tendered the planning procedure. Construction was realised by SNHBM, between 2013 and 2017.

Required resources

Municipalities implementing such approaches must invest more time and money. If a developer creates the PAP, the role of the municipality is limited to the approval procedure. After that it has limited possibilities to influence future use of the plot.

The project illustrates that municipalities creating PAP independently have a strong planning tool at hand. This pre-supposes willingness to invest time and effort. The municipality of Mondercange had to allocate financial resources and labour input to manage the process. The process included managing the procurement and coordinating the cooperation with SNHBM. The urbanistic office (service urbanisme) of Mondercange was in charge of the process. Such a planning process comes at a cost but provides significant added-value for the municipality by making it possible to actively shape developments.

Results

As the municipality has created the PAP, it was possible for the administration to lay out provisions for the site. Mondercange thus created a new district to its own design with 55 single family houses within the municipality. The price per square metre for these houses is lower than the average price for housing in the country of Luxembourg. New and old residents also benefit from a new, large park that was built in the centre of the new district.

Experiences, success factors, risks

The approach is a positive way to develop municipal land. Generally, this requires more efforts (for coordination and procurement of the planning process) but it provides significant opportunities for municipal administrations to actively shape the urban pattern. The case of Mondercange also illustrates how political priorities in the field of affordable housing can be realised through concrete projects in the municipality.

Conclusion

A stable political and administrative framework for local experts and urban planners is key. Such projects usually take longer than a single legislative period. Additionally, the project shows a way of cooperating between different levels of decision-making. SNHBM, a national actor and the municipality of Mondercange as the local stakeholder, have managed to create affordable housing, bypassing market influences. This is important, as private developers are usually less motivated to create affordable housing.

Contacts

Municipal administration of Mondercange: commune@mondercange.lu