In the dynamic and pressured landscape of Luxembourg’s housing market, innovative solutions are essential to address the growing challenges of affordability and community integration. One promising approach is the housing cooperative model, which offers an alternative to traditional homeownership and renting. These cooperatives emphasise communal living, ecological responsibility, and affordability, providing a sustainable and inclusive solution to the housing crisis. Cedric Metz, the president of Adhoc, Luxembourg’s first non-profit housing cooperative, offers valuable insights into the value of housing cooperatives, their role in Luxembourg’s housing market, and the future prospects for such initiatives in the country.

What are housing cooperatives and what is their added value?

Housing cooperatives are organisations that create and manage housing collectively, based on principles of self-help and self-responsibility. Members of a cooperative actively participate in the planning and design of their living spaces and social interactions. The primary value of these living arrangements lies in fostering community and social cohesion. Additionally, the housing is often constructed with ecological considerations and provides affordable accommodation below market rates, contributing to social stability and promoting sustainable living. Housing cooperatives are one form of community housing, next to co-living, rental house syndicates, and communities of owners. People who wish to live together join forces and jointly operate a building in whose flats they are granted the right to live. If economic profits are excluded, the co-operative operates on a non-profit basis.

What is the state of the housing market in Luxembourg and what role do housing cooperatives play?

The housing market in Luxembourg is characterised by high prices and a shortage of affordable housing. Demand far outstrips supply, leading to increasing rents and property prices. Housing cooperatives offer a valuable alternative in this context. They could create affordable housing and promote new forms of communal living, and like Adhoc can promote and raise awareness about the relevance of members not only receiving housing but also participating in the planning and design of their living environments. This potentially fosters a high level of social integration and mutual support.

What challenges do housing cooperatives and alternative housing models face in Luxembourg?

Housing cooperatives and alternative housing models are facing several hindrances in Luxembourg. One major issue is financing. Since these projects are often non-profit, accessing traditional funding sources can be difficult. Additionally, there is a significant need for political support. The housing market is heavily dominated by economic interests, making it challenging to implement socially oriented housing projects. Directly linked to that, the finding and acquisition of land depicts a significant challenge for implementing alternative forms of housing initiated by housing cooperatives due to low land availability, zoning restrictions and limited financing models. It is important to raise awareness among the public and decision-makers about the benefits of these housing models, and to provide them with adequate tools and competences to guide and support such projects from finding a site over adequate financing to facilitating the integration in the existing neighbourhood.

How does Adhoc operate?

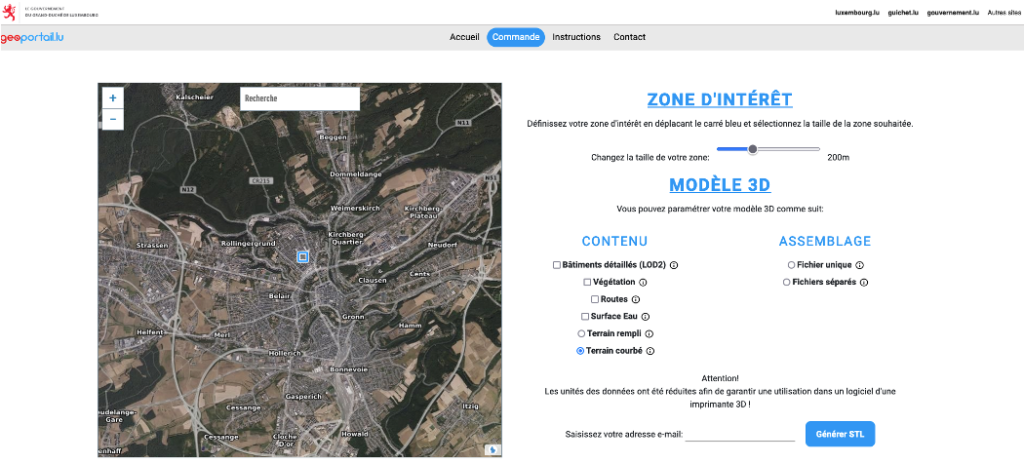

Adhoc is a non-profit housing cooperative dedicated to promoting new housing forms and developing cohousing projects. In general, the cooperative provides members with housing that is ecologically built and socially oriented. Members actively participate in the planning of their homes and the structuring of their communal living. A recent pilot project of community housing in Luxembourg’s business district Kirchberg in cooperation with the public developer Fonds Kirchberg was shut down in beginning of 2021. Fonds Kirchberg established of conditions for the site Réimerwee that Ad-Hoc, as a non-profit cooperative, could not meet, such as selling the apartments and selecting residents based on social status. Thus, Adhoc decided not to participate in the tender and will instead focus on promoting social and ecological housing projects. Additionally, the housing cooperative advises those interested in setting up cohousing projects and informs the public and policymakers about the benefits of communal living. Currently, Adhoc is working on a collaborative housing project in Weiler-la-Tour.

What support do you see from local authorities and the government?

Political support is essential for the successful implementation of housing projects like those of Adhoc. Municipalities and the government should provide financial resources and establish legal frameworks that facilitate the creation and operation of housing cooperatives. Recognising and promoting the benefits of communal living models is crucial as well as encouraging non-profit organisations as relevant actors on the housing market. This does not only include financial support but also the provision of land, the adaptation of building regulations and adapted public procurement such as concept awarding. Additionally, capacity building regarding technical and regulatory expertise within the municipalities could support housing cooperatives, e.g. through counselling centres for those interested in the foundation process.

What is the future outlook for housing cooperatives in Luxembourg?

The future outlook for housing cooperatives in Luxembourg is promising but also challenging. If the demand on the housing market and political will for communal living is not increasing, it will remain difficult to implement alternative forms of housing. Rising housing costs and a desire for sustainable and socially integrated living contribute to increasing interest in alternative housing models. Adhoc is pursuing an alternative way, demonstrating that communal living is not only possible but also desirable. However, it is important that political frameworks continue to improve to provide sustainable support for these housing models.

Contact

Adhoc: info@adhoc.lu

References

Interview by CIPU with Cedric Metz, 24th May 2024

Adhoc (English, French, German): https://www.adhoc.lu/