In the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, 2 + 3 = 1!

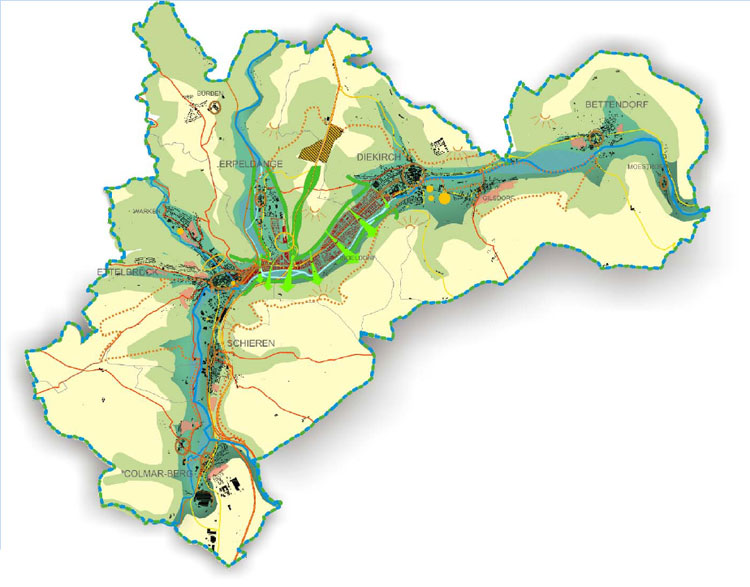

The cities of Ettelbruck and Diekirch, both located in the North of the Grand Duchy, are not far from another. The borders of the two cities are only 2 kilometres apart. Their settlement structure and those of the three neighbouring municipalities form a nearly continuous urban fabric. Many decision-makers have raised the question of why not merging forces and territory and creating the new capital city of the North?

Merging the five municipalities into a new economic powerhouse of the North, the so-called NORDSTAD, has been discussed for a long time. Two masterplans were developed, detailing roughly the urban concept for the existing settlements and earmarked areas that will be urbanised.

For various reasons, the idea to create the NORDSTAD has not yet materialised: municipal mergers and the creation of a new city need to be well thought out and the individual steps take time. One of the main hurdles was overcome in summer 2020, when all five mayors signed a memorandum of understanding to become the NORDSTAD. With their signature, the mayors have entrusted a municipal syndicate to further the idea of creating the new city. Thus, it is not a question of ‘if’ but of ‘when’ they will become the NORDTAD.

But how does one realise 2 + 3 = 1?

The typology and structure of buildings in Ettelbruck and Diekirch features low densities and pays tribute to their 8,800 and 6,800 inhabitants. Many single-family houses, number of floors seldomly exceeding five stories and a rather old building structure characterise the urban pattern. The three neighbouring municipalities Bettendorf, Erpeldange and Schieren feature many single-family houses. To transform the cities and the municipalities into one major urban pole, a lot of yet unused land will be developed.

When planning for the creation of new districts or new cities in Luxembourg, planners and architects opted for high-density structures during the past. The ‘Belval’ district in Esch-sur-Alzette and the ‘Kirchberg’ district in Luxembourg City are two examples. What makes them distinct of the NORDSTAD is that they are extensions of existing urban tissues with large numbers of inhabitants.

NORDSTAD will be different: Ettelbruck and Diekirch are small cities and high-density developments risk of destroying the areas’ properties and characteristics. For creating the NORDSTAD, a new type of ‘urbanity’ is necessary.

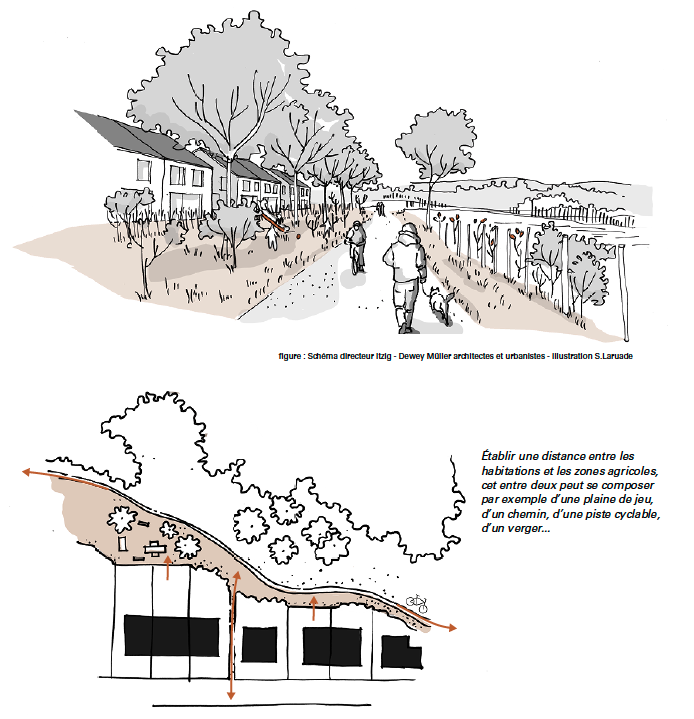

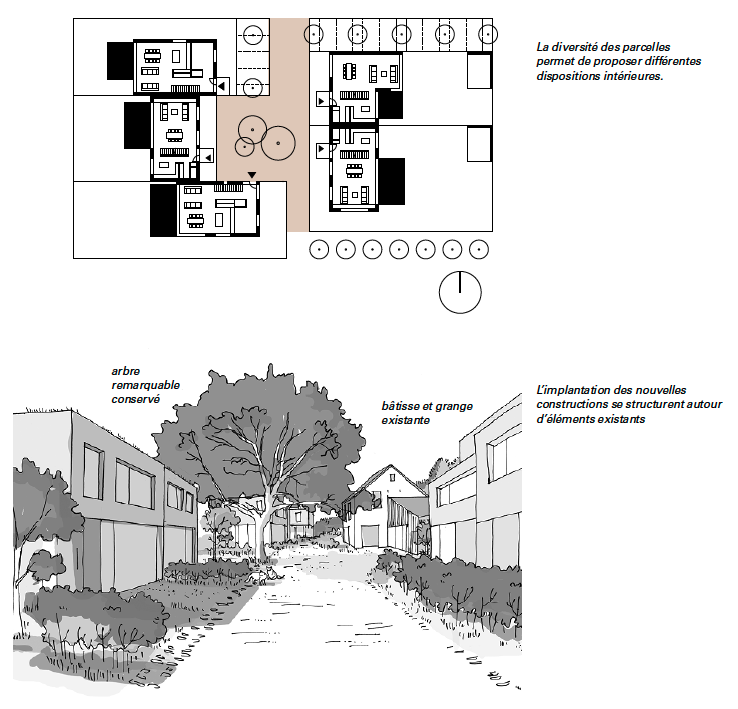

The new type of urbanity for the development of the NORDSTAD needs to meet different criteria: it needs to avoid ‘over-urbanisation’ and ensure high quality of life for future and current residents, provide adequate housing and public places and ensure the integration of existing districts into the new settlement pattern. The village-character of the two cities needs to be preserved for any future development. And finally, a major challenge planners and architects need to solve is “How to create ‘urbanity’ from the drawing board for the areas that ought to be developed?” The reflections and plans drawn up for the NORDSTAD have answered important questions that resulted in a lot of good practices.

Projects like the NORDSTAD, where a significant amount of fallow land is being developed, have become a frequent encounter in Luxembourg. Decision-makers, planners and architects need to make choices at many different levels, from the local land-use plan down to individual buildings. Especially in smaller municipalities with limited staff and expertise in urbanising areas, support and guidance was required, helping municipalities in making better choices.

In comes the so-called “Planungshandbuch”, a guideline for the urbanisation of cities and villages, developed at the example of NORDSTAD. The term is German for ‘Planning Manual’ and the document functions as such: it gives concrete guidance on the future looks, feels and properties of areas that ought to be developed. It is targeted at planners, architects, technicians, decision-makers as well as citizens. The ‘Planning Manual’ is structured in nine overarching chapters that address several topics when planning in urban areas: urban development, functional mix, building layout, public infrastructure, mobility, parking, layout of public spaces, nature protection and quality of housing. Under all these topics, the manual provides concrete design ideas and recommendations in an illustrative way.

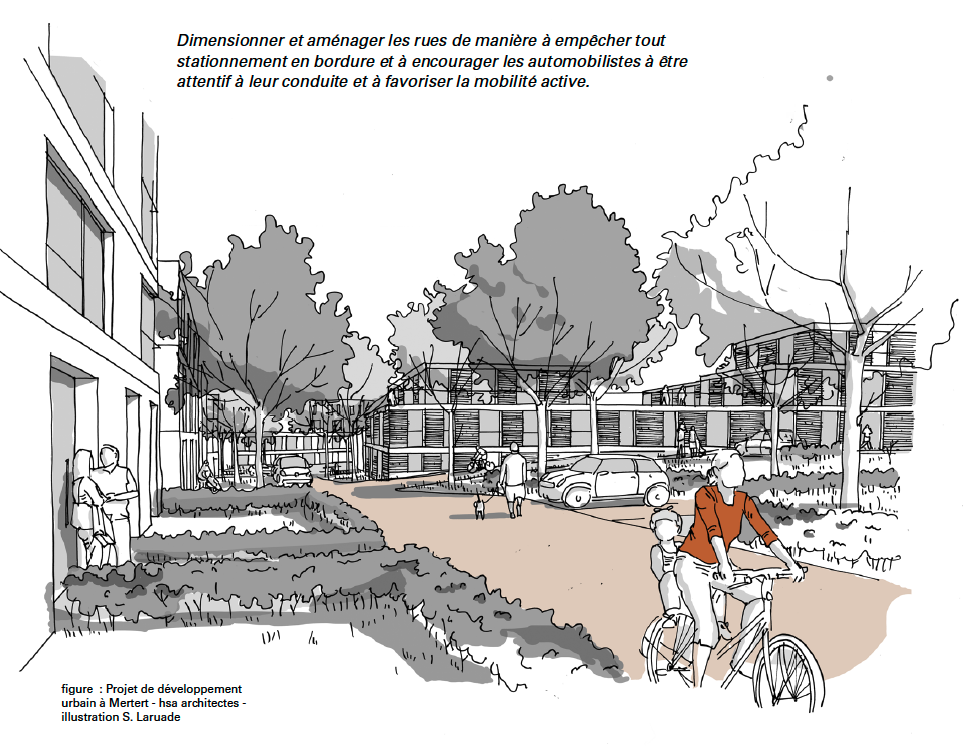

The illustration shows a proposed layout for public and semi-public areas from the ‘Planning Manual’. Open places in front of building entrances allow residents to meet and to chat. Narrow streets and limited parking slots while providing good access via soft means of transport, reduces need for motorised forms of mobility. Source: Planungshandbuch, 2021.

The presented ideas were drawn from the experience of urban planners in the NORDSTAD and in other Luxembourgish convention areas. Convention areas are associations between the state and municipalities to ensure territorially integrated development across administrative levels and borders in the country. The ‘Planning Manual’ thus draws from the knowledge and lessons learned from concrete examples.

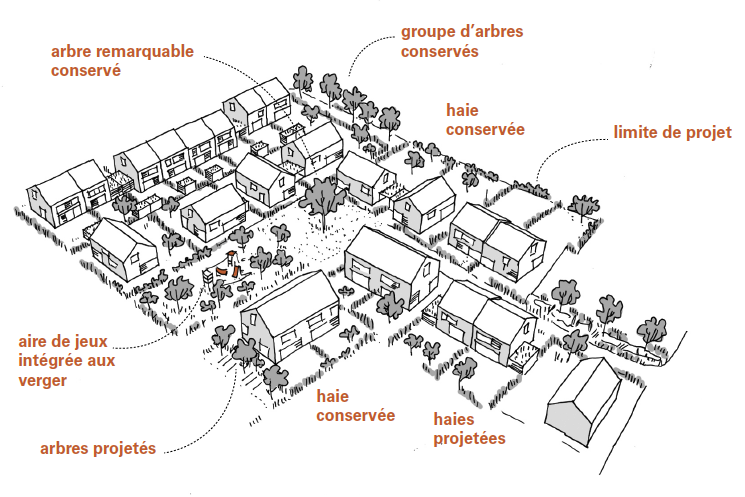

The illustration shows a proposed green space concept for districts from the ‘Planning Manual’. A mix of private and public gardens creates privacy and areas where residents can meet. Existing trees and hedges are integrated into the districts. Source: Planungshandbuch, 2021.

The document is unique as it gives guidance to planners and architects long before decisions on the exact layout of new districts are taken. Even if districts are planned and implemented by different planners and architects, they will have similar looks and feels and a common character. This will convey a feeling of a common identity amongst future residents of different districts. Such a guideline also allows to include important features such as quality of life or sustainability from the very beginning in district development.

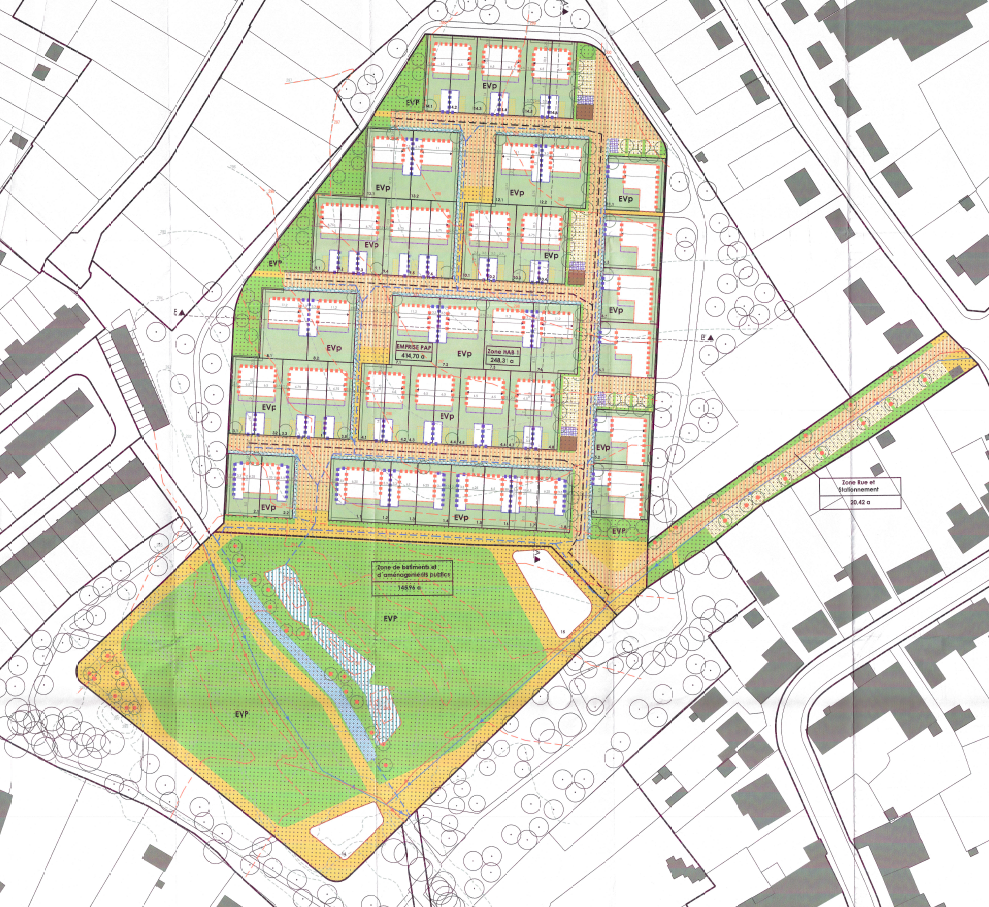

The illustration shows a proposed concept to combine private, mixed and public from the ‘Planning Manual’. Small access paths that connect several private gardens and shared meeting areas for neighbours create transition areas between private and public gardens. Source: Planungshandbuch, 2021.

Also, the ‘Planning Manual’ with its comprehensible texts and numerous illustrations gives planners a new tool for public participation. Breaking down urbanistic guidance from complex 2D and 3D renderings to drawings and pictures allows residents much easier to understand urban design. Residents can thus raise their voice and work together with architects and planners on integrating their wishes and need in the future development. In turn, this helps to reduce often observed phenomenon like ‘NIMBY’ (‘Not In My Back Yard’) and increases identification of residents with their future districts.

If you are interested further, please find here the complete planning manual, allowing to get a more comprehensive picture of recommendations and guidance to urban development in Luxembourg.

In conclusion, the “Planungshandbuch” provides orientation to planners, citizens and decision-makers on the future looks and feels of districts that ought to be developed. It clearly points at good practices and things to avoid and capitalises the knowledge created during discussions of planners, architects and decision-makers in the framework of the NORDSTAD project. The manual allows to visualise and include elements of urban design from the very beginning into planning processes. This helps to create high quality urban environments across the country, respecting principles of a sustainable urban development and ensures a high quality of life in future urban districts.