The Master Programme for Spatial Planning in Luxembourg, known as “Programme directeur d’aménagement du territoire” (PDAT) 2023, is the central element of the country’s spatial planning policy. Serving as a framework for a sustainable development of the national territory and for enhancing the quality of life of all citizens, the PDAT defines an integrated strategy for sectorial policies with a territorial impact and defines guidelines, objectives and measures for the government and municipalities. The newly adopted PDAT (21 June 2023), which was prepared by the Department of Spatial Planning in cooperation with an interministerial working group, builds upon a large public participation process in 2018 and the international consultation “Luxembourg in Transition” in 2020—2022.

Structure and objectives

In order to frame the strategy, objectives and measures, the PDAT was developed in accordance with the following four guiding principles:

- Increasing the resilience of the territory

- Safeguarding territorial, social and economic cohesion

- Ensuring a sustainable management of natural resources

- Accelerating the transition of the territory to carbon neutrality

Based on those guiding principles, three policy objectives and a cross-cutting objective have been identified, addressing the development issues highlighted in the spatial analysis as well as the challenges imposed by climate, environmental, geopolitical and health crises:

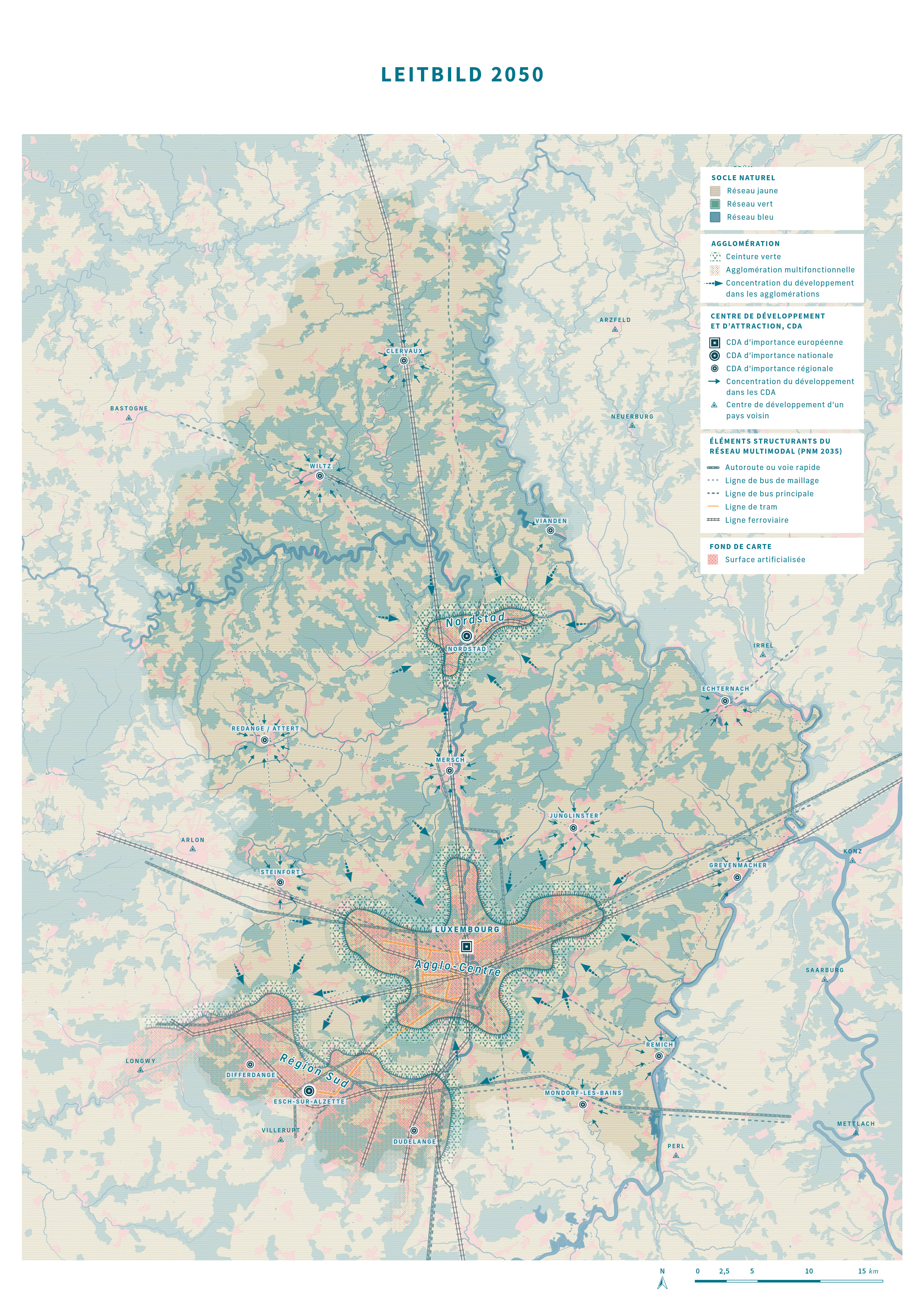

1. Concentration of development in the most suitable places: Central to the PDAT’s mission is guiding sector policies and supporting municipalities in locating essential functions and services in the most suitable places. This aims to facilitate access to services, anticipate and reduce mobility needs as well as plan for critical infrastructure.

By guiding future development, the PDAT enables efficient infrastructure planning and a cost-effective implementation of sector policies. The territorial strategy encompasses an urban hierarchy based on Central Places (centres de développement et d’attraction, CDA), which is supposed to steer the spatial distribution of population (i.e. development) and employment growth (i.e. attraction) in a sustainable manner.

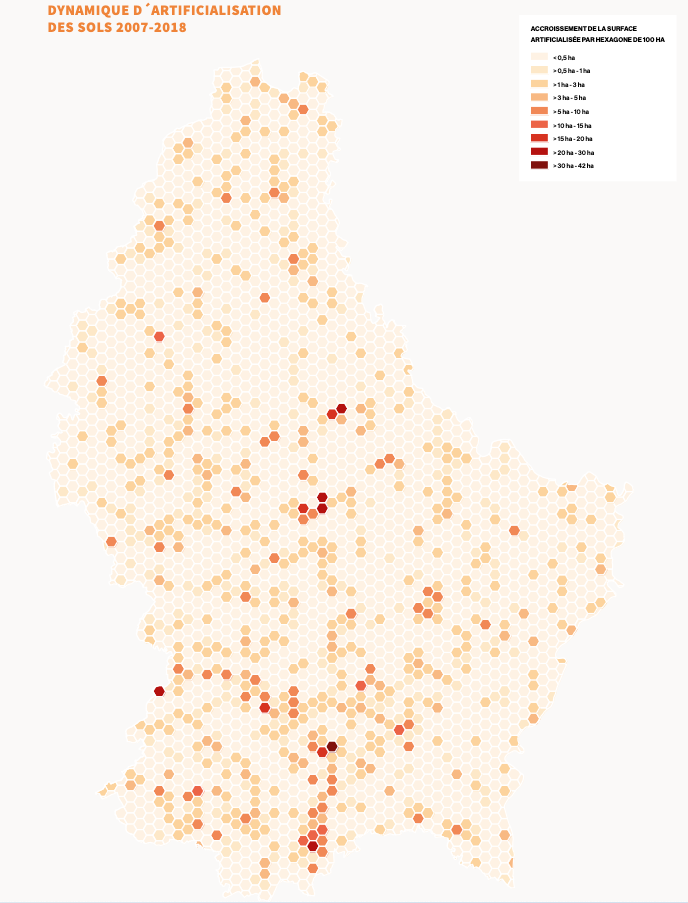

2. Reducing land take: The PDAT focuses on limiting the process of converting natural, agricultural or forest land into built-up areas. Decreasing land take offers several benefits, including mitigating the effects of climate change, preserving natural and semi-natural areas, minimising flood risks, protecting biodiversity, and fostering carbon sequestration. The goal is to gradually reduce land take from by 2035 and tend towards no net land take (zéro artificialisation nette du sol) by 2050.

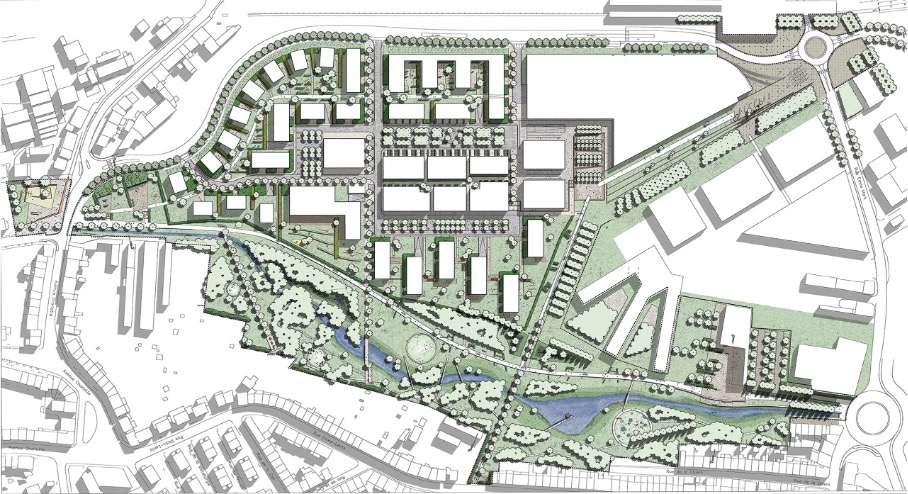

To achieve this, the PDAT puts forward a planning culture that promotes urban regeneration, multifunctionality and efficient land management.

3. Cross-border spatial planning: Taking into account the functional linkages between Luxembourg and its cross-border functional region, the PDAT recognises the need for a concerted territorial development in the Greater Region (Grande Région). To address ecological and climate transition challenges, the Master Programme promotes territorial development strategies for cross-border functional areas, consultation with neighbouring regions in the framework of planning processes, and cross-border resource management.

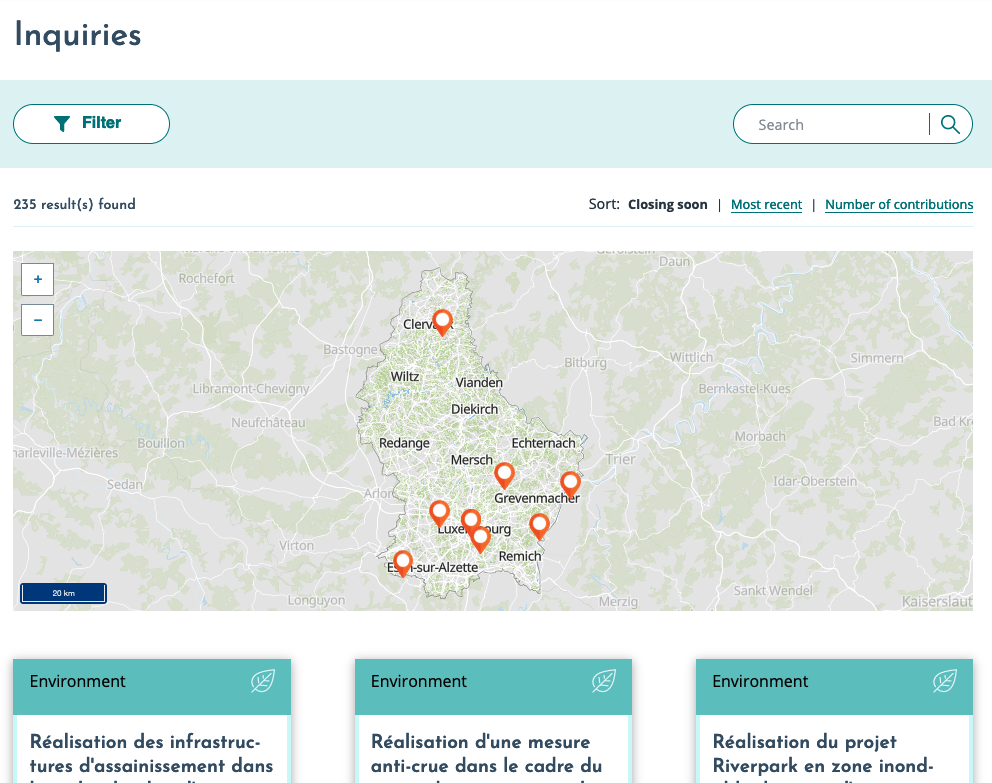

4. Collaborative Governance as a cross-cutting objective: In the PDAT, governance is considered to be a cross-cutting objective, emphasising the coordination required for effective spatial planning. This is meant to happen horizontally across sector policies, vertically between the State and municipalities, as well as through public participation.

Time Horizon

The PDAT2023 is meant to unfold in two phases: 2023-2035 and 2035-2050. The first period until 2035 will act as a transition phase, which contributes to reversing the current development trends. Actions will focus on identifying and adopting instruments for the implementation of the Master Programme as well as initiating pilot projects and stakeholder connections.

The second phase, from 2035 to 2050, will ensure a steady transition and reverse the trends in question by the implementation of the strategies, while monitoring the developments as well as adapting approaches as needed.

Implementation

In order to achieve the above-mentioned policy objectives in the given timeframes, two territorial strategies have been developed at different scales. First, the national territorial development strategy “Leitbild 2050” envisions a carbon-neutral and resilient territory, emphasising green, yellow and blue networks, the concentration of development in accordance with the urban hierarchy, and a sustainable mobility. This national territorial development strategy has also been broken down to so-called action areas (espaces d’action) at a functional-regional level. In this context, territorial visions for the three urban agglomerations have also been developed. Second, the territorial development strategy at the level of the Greater Region promotes cooperation in cross-border action areas, in accordance with the Interreg VI Greater Region programme. This cooperation fosters integrated territorial development in cross-border functional areas, complementing previous approaches by addressing challenges linked to the environment and natural resources. The implementation of strategies will be fostered through the adaptation of existing regulatory instruments and the potential creation of new ones.

Conclusion

The Master Programme for Spatial Planning in Luxembourg sets a forward-looking and ambitious territorial vision. By addressing climate change, resource preservation and sustainable growth, the PDAT paves the way for the ecological transition of the territory. Through clear strategic objectives and cross-sectoral coordination, Luxembourg is taking a further step towards sustainable development and enhancing citizens’ quality of life.

References

Master Programme for Spatial Planning in Luxembourg – “Programme directeur d’aménagement du territoire” (PDAT) 2023 (French): https://amenagement-territoire.public.lu/content/dam/amenagement_territoire/pdat-programme-directeur-damnagement-du-territoire-4072023.pdf

Spatial planning portal (French): https://amenagement-territoire.public.lu/fr/strategies-territoriales/programme-directeur.html