In October 2020, a significant milestone was achieved in the southern Luxembourg region, as 11 municipalities under the PRO-SUD syndicate joined the UNESCO Biosphere network, a label renowned as educational hubs for sustainable development. This move accelerates a series of initiatives aimed at actively fostering sustainable development.

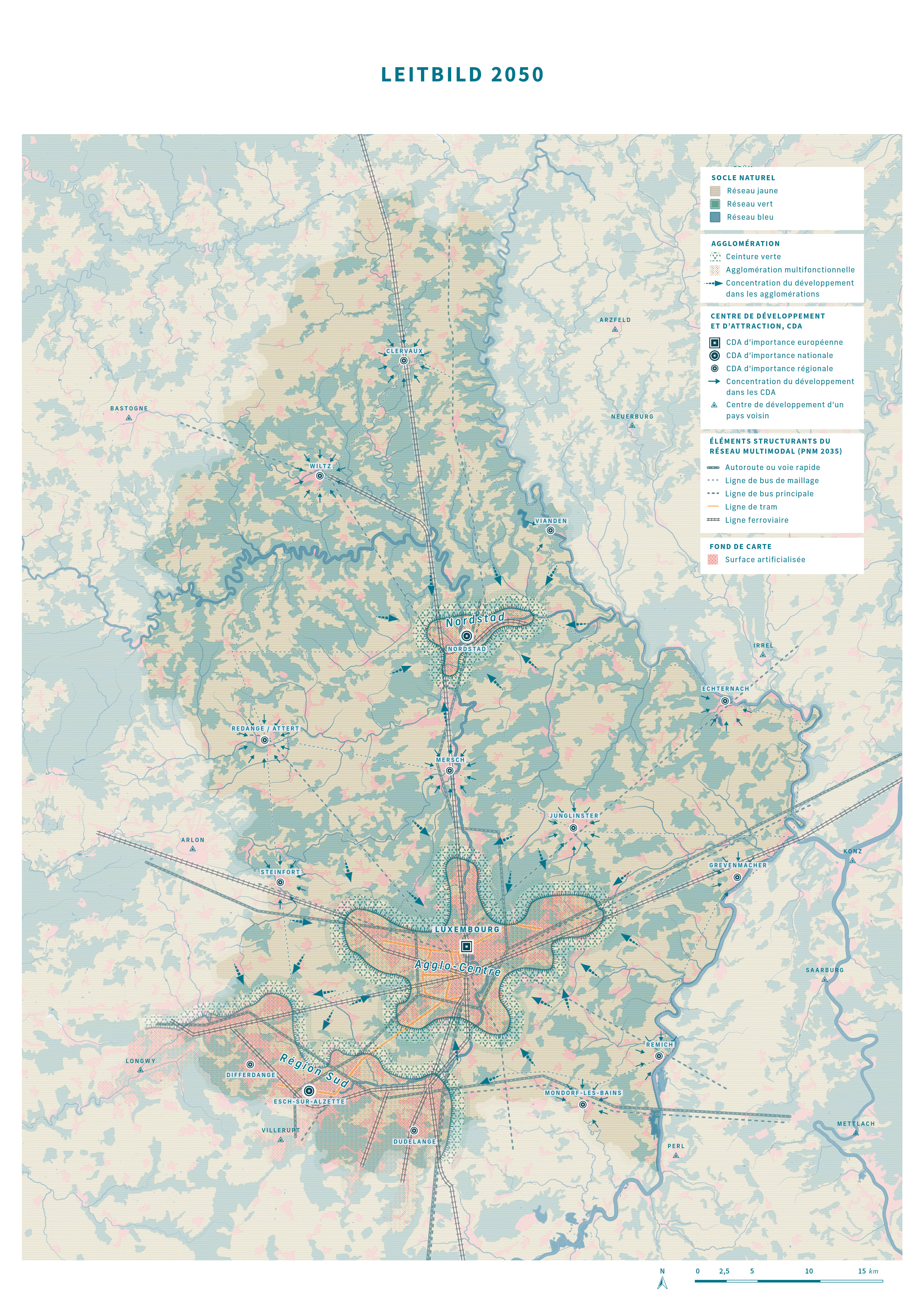

One of the key initiatives that followed was the collaborative formulation of a “territorial vision” for the region, harmonised with the objectives outlined in the Luxembourgish National Territorial Development Plan (PDAT). The “territorial vision” strategy is taking shape with the Mission Zero Carbon – 11 municipalities for the ecological transition launched in April 2023 and marked by the signing of a Letter of Intent by PRO-SUD’s 11 municipalities, the Minister of Spatial Planning, and the Minister of Environment.

Aim

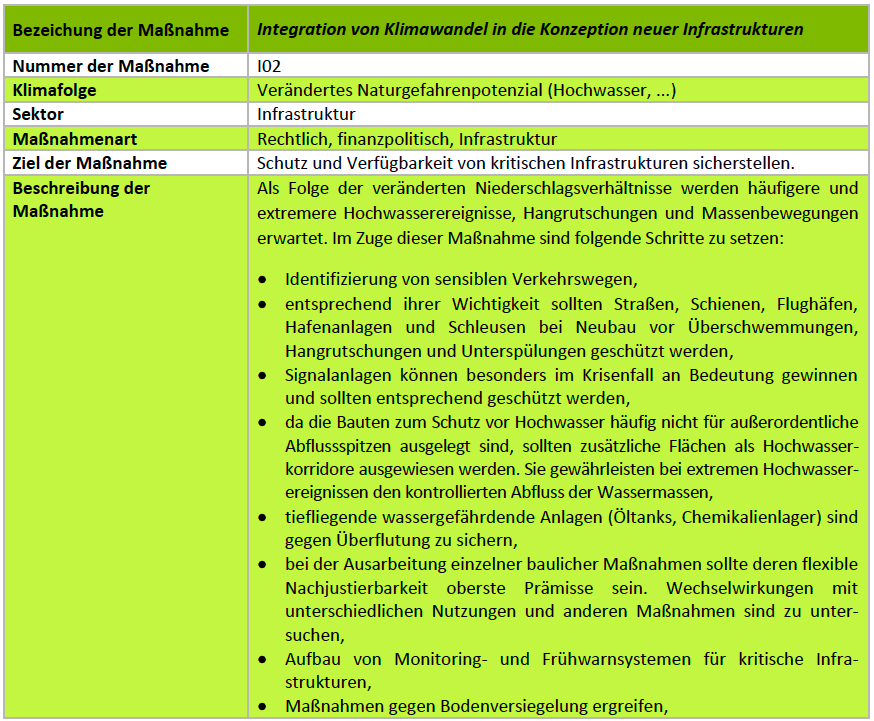

The primary goal of Mission Zero Carbone is to foster regional collaboration towards achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, in alignment with the Luxembourgish national territorial development plan (PDAT). To realize this ambition, a range of strategies has been identified, encompassing:

- Reducing energy consumption: Advocating for energy-saving practices and technologies across public sectors.

- Increasing renewable energy usage: Promoting the adoption and integration of renewable energy sources, such as solar panels.

- Enhancing energy efficiency through regional energy planning.

- Promoting sustainable mobility: Advocating for active transportation modes like cycling and walking and enhancing public transport infrastructure.

- Safeguarding and restoring natural habitats: Ensuring the preservation of existing ecosystems and rejuvenating degraded areas to amplify their carbon sequestration potential.

- Educational programs engage students, teachers, and cultural associations in the ecological transition, fostering active participation and awareness to drive sustainable change.

A first concrete project of this regional approach is the bioclimatic map launched in partnership with the Luxembourg Institute of Sciences and Technology (LIST) and Geonet by acquiring vital data and conducting precise analyses on the urban bio-climate of the region.

Concurrently, the Bioclimatic Mapping Project is committed to assessing the urban bio-climate in the southern Luxembourg region. The recommendations derived from this mapping effort will be closely associated with PRO-SUD’s involvement in the Cool Neighbourhood Interreg Northwest programme, which is designed to address urban heat challenges. This initiative marks a significant advancement in fostering the development of sustainable and resilient cities through meticulous data collection and analysis. The results will be publicly available towards the end of 2024.

Genesis and Composition

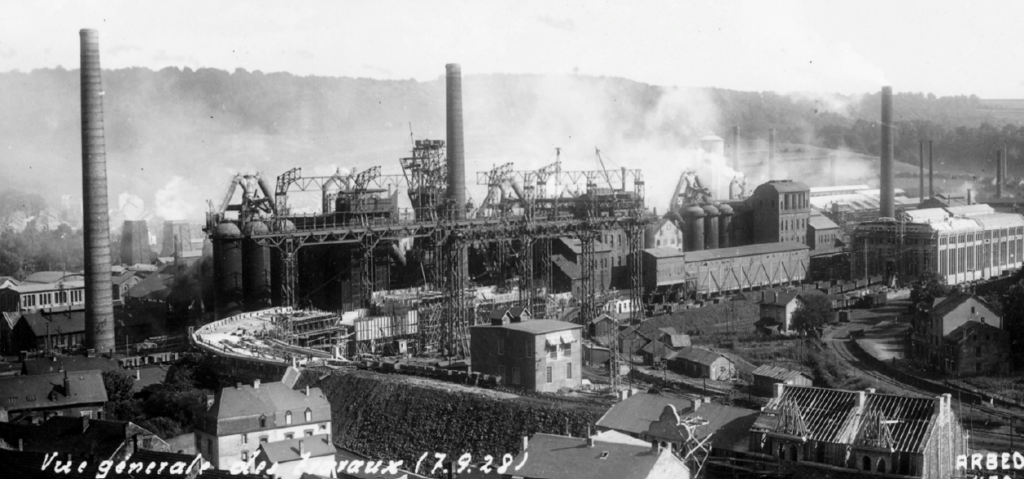

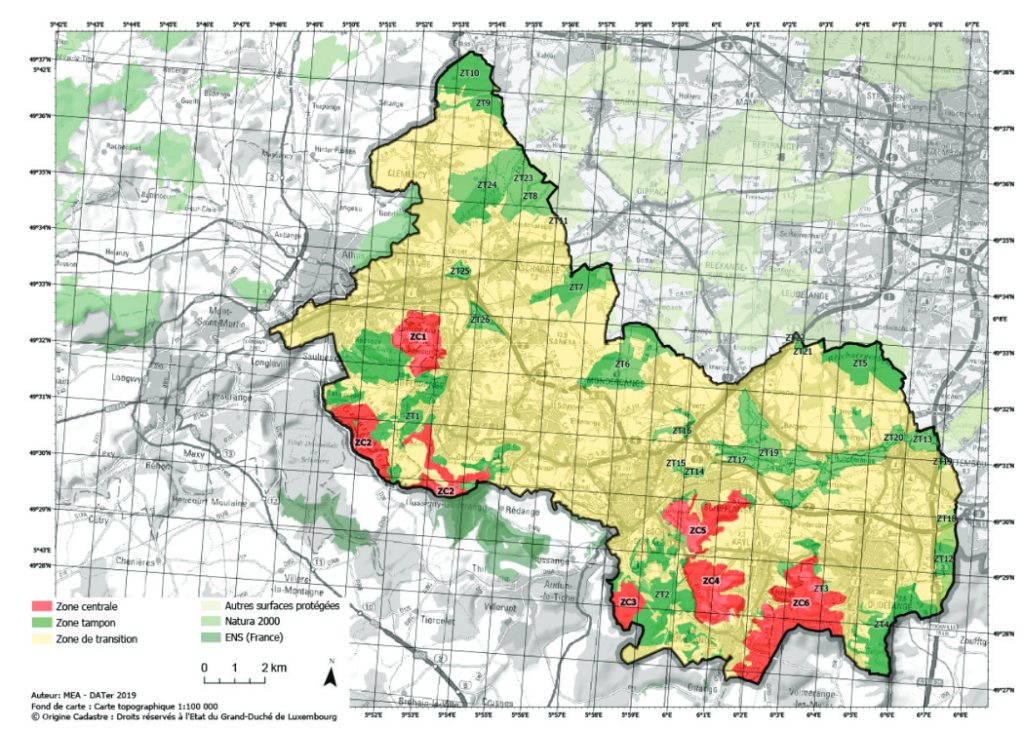

After the Luxembourg UNESCO Commission began discussing the first biosphere reserve in the Grand-Duchy in 2016 and followed by 4 years of multidisciplinary work to complete the application, the Minett region was officially recognized as such in October 2020, making Luxembourg part of the scientific Man and the Biosphere (MAB) programme. This programme promotes the conservation of biodiversity by engaging inhabitants, educating, researching, and supporting regional initiatives for sustainable development. The Minett Biosphere presents a fascinating juxtaposition: abandoned mines transformed into biodiversity havens, alongside ongoing human activity within dedicated transition zones. The Minett biosphere encompasses a region significantly impacted by iron ore extraction, leaving behind a distinct industrial legacy evident in its topography and cultural heritage.

PRO-SUD coordinated the application process and organized citizen consultations. Founded in 2003, the syndicate is a regional development union comprising 11 municipalities in southern Luxembourg. PRO-SUD, with the support of the Spatial Planning Department, is committed to promoting sustainable development in the region through various projects encompassing economic development, environmental protection, and social well-being.

Activities

The Minett UNESCO Biosphere advocates for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development, engaging citizens in educational efforts and research. It offers logistical assistance to projects focused on environmental education, multidisciplinary, regional and cross border collaboration with a commitment to fostering socio-culturally and environmentally sustainable economic and human development.

The post-industrial landscape of the region highlights the potential for ecological resilience, with diverse flora and fauna now flourishing in former mining sites. However, managing the delicate balance between environmental protection and ongoing growing human activity remains a huge challenge. To address this, the biosphere employs a strategic zoning system comprised of:

- Core areas (zone centrale): Dedicated to research and conservation, strictly limiting human intervention.

- Buffer zones (zone tampon): Surrounding core areas, these zones aim to minimize the impact of human activities.

- Transition areas (zone de transition): Allow responsible human activities like agriculture and development.

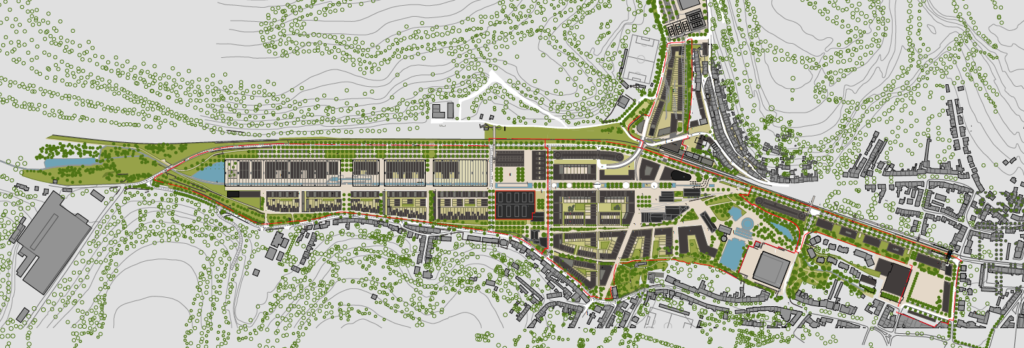

The territorial vision delineates a comprehensive developmental blueprint for the Minett region, encapsulating six pivotal objectives to ensure project alignment with overarching sustainable development objectives:

- Sustainable development: Pursuing a holistic approach that integrates environmental, economic, and social dimensions.

- Territorial cohesion: Mitigating socio-economic disparities across the region.

- Attractiveness and vibrancy: Augmenting the quality of life of residents and businesses.

- Ecological transition: Attaining climate neutrality and safeguarding biodiversity.

- Governance and participation: Advocating for participatory decision-making processes and citizen involvement.

- Resilience and adaptability: Anticipating and preparing for future challenges to ensure sustained regional viability.

The collaborative initiative, Mission Zero Carbone, epitomizes this vision, rallying the 11 municipalities within the Minett Biosphere towards achieving regional carbon neutrality by 2050. Each municipality formulates its action plan in alignment with the mission’s overarching objectives, addressing localized challenges and opportunities. Collaborative endeavours facilitate knowledge exchange, resource consolidation, and joint implementation of impactful projects across the region.

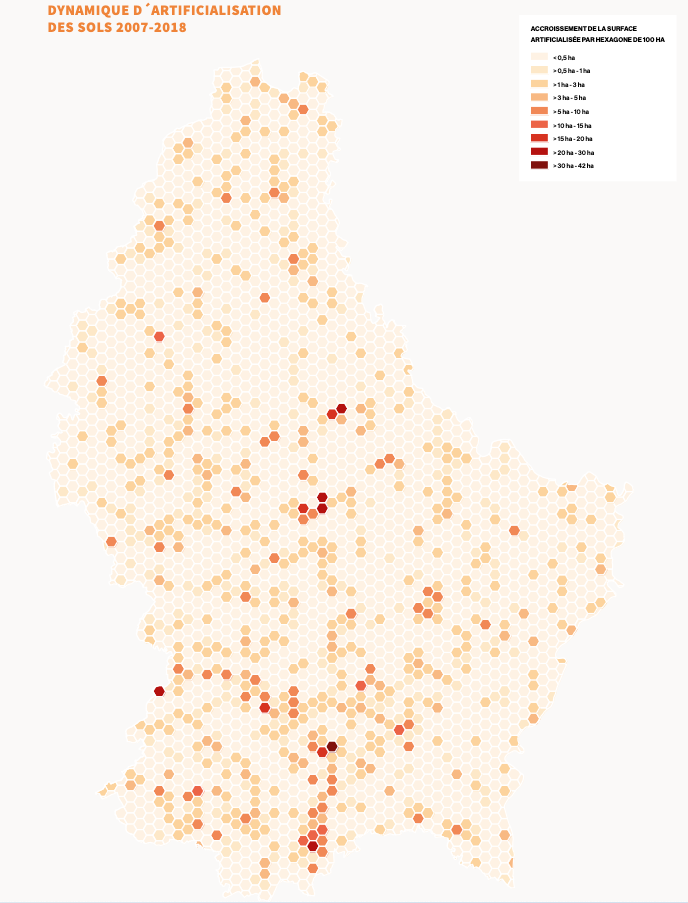

An initial project under this framework is the Bioclimatic Mapping initiative, generating pivotal data and analyses on the urban bio-climate of the Minett Biosphere. Initiated in response to a municipality architect’s request for more precise bioclimatic data to inform sustainable urban development strategies, this mapping project employs climate scenarios—specifically the RCP4.5 scenario—to project climatic conditions. Utilizing the 25th and 75th percentiles of temperature distribution (17.5°C and 19.5°C, respectively) instead of mean values, it offers a nuanced understanding of potential climate impacts.

PRO-SUD has commissioned the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (LIST) to spearhead this project, leveraging diverse methodologies such as remote sensing, on-site measurements, and citizen science initiatives over an 18-month duration until the project’s conclusion in late 2024. The resultant data will inform the development of a comprehensive climate model for the region, guiding decision-makers in formulating effective emissions reduction strategies.

Outlook

Mission Zero Carbone represents a significant challenge, yet it is pivotal for the Minett Biosphere to attain its climate goals and contribute to the Territorial Vision. he Bioclimatic Map, furnishing invaluable data and analysis, plays a crucial role in guiding strategic actions and ensuring the first mission’s success to develop regional collaboration between the 11 municipalities. For those interested in the UNESCO Biosphere in southern Luxembourg, the website provides insights into its initiatives for achieving climate neutrality and other impactful projects. Further information can be found on the Minett Biosphere’s website.

Contact

Gaëlle Tavernier: prosud@prosud.lu

References

Minett Biosphere: (English, French and German): https://minett-biosphere.com/en/

Mission Zero Carbone: (English): https://minett-biosphere.com/en/news/mission-zero-carbone-kick-off-meeting-3/

Vision territorial (French): https://minett-biosphere.com/lu/projects/vision-territoriale-3/

Project ClimProSud (English and French): https://www.list.lu/fr/recherche/projet/climprosud/?no_cache=1&tx_listprojects_listprojectdisplay%5Barchive%5D=&cHash=ac5bde4a60223253a34e3f5ad42ffb87 Analysing the Urban Bioclimate of the South (Project ClimProSud (English, French, German, Luxembourgish): https://minett-biosphere.com/en/news/analysing-the-urban-bioclimate-of-the-south/