The National emergency organisation plan (Plan National d’Organisation des Secours – PNOS) introduced under Luxembourg’s revised Civil Security Law of 27 March 2018, is an important initiative to enhance the country’s emergency response capabilities. By outlining clear objectives for the Luxembourg Fire and Rescue Corps (Corps grand-ducal d’incendie et de secours – CGDIS), the PNOS provides a structured approach to assessing risks, planning responses, and improving operations.

Objectives

The PNOS aims to systematically assess risks across Luxembourg and to define intervention objectives for the CGDIS. Its objectives include setting clear expectations for emergency services to meet the needs of residents and visitors, planning the development of the CGDIS through 2025 with a focus on adapting to changing risk scenarios, and shaping the organisational structure of CGDIS to ensure efficient recruitment, training, and resource allocation. These elements work together to ensure that emergency services remain effective and responsive to evolving challenges.

Background

Luxembourg’s socio-economic growth, characterised by urbanisation, population increase, and technological change, highlighted the need for a more proactive approach to civil security. The Civil Security Law of 2018 laid the foundation for the PNOS to address gaps in emergency planning and response. Between March and June 2021, municipalities were consulted to align local, regional, and national priorities. This collaborative approach also considered emerging challenges, including climate change and industrial risks.

What’s inside?

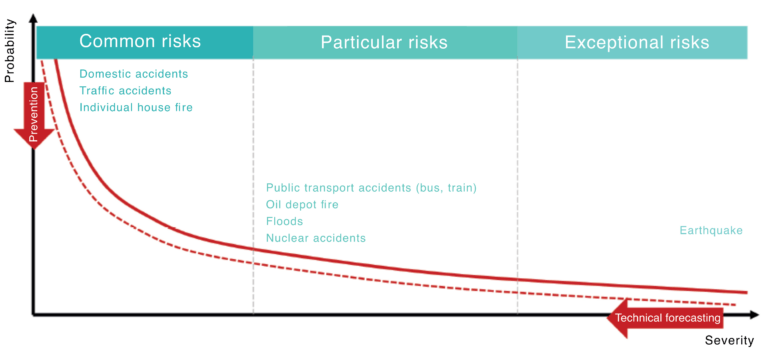

The PNOS is built upon a detailed understanding of Luxembourg’s structural characteristics, such as its geography, demographics, transport infrastructure, and economic activities. These elements were key to identifying and addressing the diverse risks. The PNOS focuses on three main types of risks (see figure 1):

- Daily Risks: These are frequent but relatively minor incidents, such as medical emergencies (SAP), fires, or traffic accidents, which form the bulk of rescue operations.

- Specific Risks: These are less frequent but potentially severe incidents, such as floods, landslides, storms, or accidents involving hazardous industrial facilities, including SEVESO-classified sites.

- Exceptional Risks: These include rare or unpredictable events, such as earthquakes, terrorist attacks, or hostile actions targeting critical institutions, including NATO and EU agencies in Luxembourg.

Figure 1 – Classification of risks and threats (translated from the original source in French: Ministry of Home Affairs: https://maint.gouvernement.lu/en/dossiers/2021/PNOS.html)

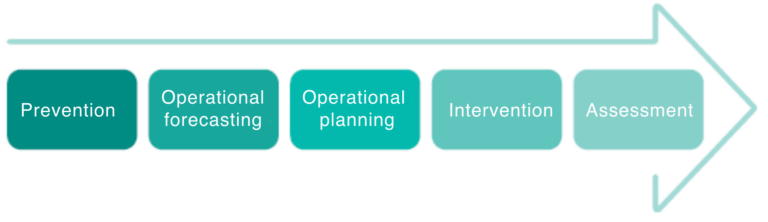

To address these risks, the PNOS sets out five key strategic functions that underpin CGDIS operations: prevention, operational forecasting, planning, intervention, and assessment (see figure 2). While the intervention function ensures direct emergency responses, the other four focus on organising and improving the CGDIS’ operational structure at national, zonal, and local levels.

This comprehensive approach also reveals the need for further organisational efforts to develop prevention measures, improve operational forecasts, and enhance planning and evaluation processes. Currently, CGDIS operates with 100 fire and rescue centres (CIS) equipped for daily risks and ten specialised intervention units (GIS) ready to address more complex emergencies. A significant number of rescue operations already achieve response times of under 15 minutes.

Figure 2 – Analysis steps of the operational coverage of identified risks (translated from the original source in French: Ministry of Home Affairs: https://maint.gouvernement.lu/en/dossiers/2021/PNOS.html)

Implementation

Building on the analysis of risks, the PNOS outlines a range of measures designed to address diverse civil security needs. These measures focus on improving emergency response efficiency, expanding operational capacity, and enhancing of prevention and preparedness across the country. The PNOS targets the following areas, aiming to build a more resilient and responsive system for all emergency scenarios.

- Risk Management: Addresses common emergencies, which account for over 75% of CGDIS operations, while also preparing for specific and more exceptional risks.

- Response Times: Aims to achieve response times under 15 minutes for 90–95% of incidents.

- Building Capacity: Bringing the total number of professional firefighters to 1,100 by 2025, including roles in operations, prevention, planning, and management.

- Upgrading Infrastructure and Equipment: Includes modernising rescue centres, communication systems, and specialised equipment for various risks.

- Promoting Prevention and Training: Encourages risk awareness through public campaigns and professional training programs.

Conclusion and Outlook

Looking towards 2025, the PNOS outlines two key priorities:

- Operational Readiness: Luxembourg’s growing population and evolving risk landscape require an increase and diversification of rescue operations. This includes addressing climate-related risks such as extreme storms, heatwaves, droughts, and new health or safety challenges arising from technological and industrial developments.

- Organisational Strengthening: Developing and implementing missing concepts will enable CGDIS to perform rescue operations efficiently and without constraints.

The PNOS represents a significant step forward for Luxembourg’s civil security. It addresses immediate challenges while preparing the country for future uncertainties. As the plan is implemented, the CGDIS will continue to improve its efficiency and resilience, ensuring the safety of residents and visitors. Ongoing evaluation and collaboration with stakeholders will help the PNOS adapt to new risks and maintain its effectiveness in protecting the nation.

Contact:

Directorate General for Civil Security: dgsc@mai.etat.lu

References

Ministry of Home Affairs (English, French, German, Luxembourgish): https://maint.gouvernement.lu/en/dossiers/2021/PNOS.html

Corps grand-ducal d’incendie et de secours: (French): https://112.public.lu/fr/organisation/PNOS.html