Frequent extreme weather events in Luxembourg in recent years have pushed climate change higher up the public agenda. The call for more public action has become louder in view of the devastating effects of recent tornados and torrential rainfall, followed by flooding and extended drought in the summer noticed by residents and visitors.

Preparing and adjusting to current and future effects of climate change, ‘climate change adaptation’, is one pillar next to climate action that governments around the globe are working on to limit the impact of climate change on societies.

Despite progress made during past years, there are critical gaps in implementation of climate action, where policy ambitions have not yet yielded necessary action. This highlights the need for clear information and guidance to streamline actions to progress towards a shared agenda for practitioners and planners. The ‘Climate Change adaptation strategy’ comprehensively promotes climate change adaptation in Luxembourg.

Rationale for action

According to IPCC scenarios, by the end of the 21st century, Luxembourg will experience today’s climate of Milan. What sounds positive at first glance has serious consequences with average annual temperature rising from 8.8 to 13.1° Celsius and rainfall increasing by 30% over the next 80 years.

These numbers should not distract attention from expectations of more frequent extreme weather events including heat stress, rainfall variability, less available freshwater, lower crop yields, lower soil quality, uncertain energy supply, increasing conflicts of use and less biodiversity. These show the current system is not yet ready to cope with climate change.

Despite these observations, climate change adaptation still appears to be a side note in Luxembourg spatial planning. With municipalities responsible for planning, state institutions depend on municipal decision makers and planners being informed and willing to work towards climate change adaptation. To become more resilient to a changing climate, more attention needs to be given to climate-change adaptation to prepare for inevitable impacts as the current system is not yet prepared.

Objective

Preventing harm to humans and natural ecosystems from climate change requires adapting the built environment. The fundamental assumptions on which local planning and developments have been based for decades have changed, especially for water availability and amount of rainfall.

Much more than simple adaptations are necessary. With changing fundamental assumptions on climate, new techniques and methods are needed. This means new methods to cope with the new reality and to adapt existing systems.

Transition is very complex. It requires modifications to the way we have planned for decades. So planning guidance is essential, along with a national reference framework to detail and measure the effectiveness of actions to induce significant change. The Climate Change Adaptation Strategy provides this guidance. It gives information from Luxembourg planners for Luxembourg planners about climate change adaptation.

Time frame

The strategy has been updated frequently since the first edition in 2012. New planning laws and regulations made an update necessary in 2016 and a new edition was published in 2018 which remains valid today. To assist local decision makers and planners, the new edition also has an implementation strategy.

Key players

The strategy has been developed by the Department for Environment of the Luxembourg Ministry of Energy and Spatial Planning, which is also responsible for implementation. It works towards the Paris Agreement and has been adopted by the Government so it applies to all government institutions.

Implementation steps and processes

The climate change adaptation strategy offers a comprehensive catalogue of measures. It covers construction and housing, energy, forestry, infrastructure, civil protection, spatial planning, agriculture, human health, ecosystems and biodiversity, tourism, urban development, water management and the economy. There are also specific recommendations on cross-cutting measures.

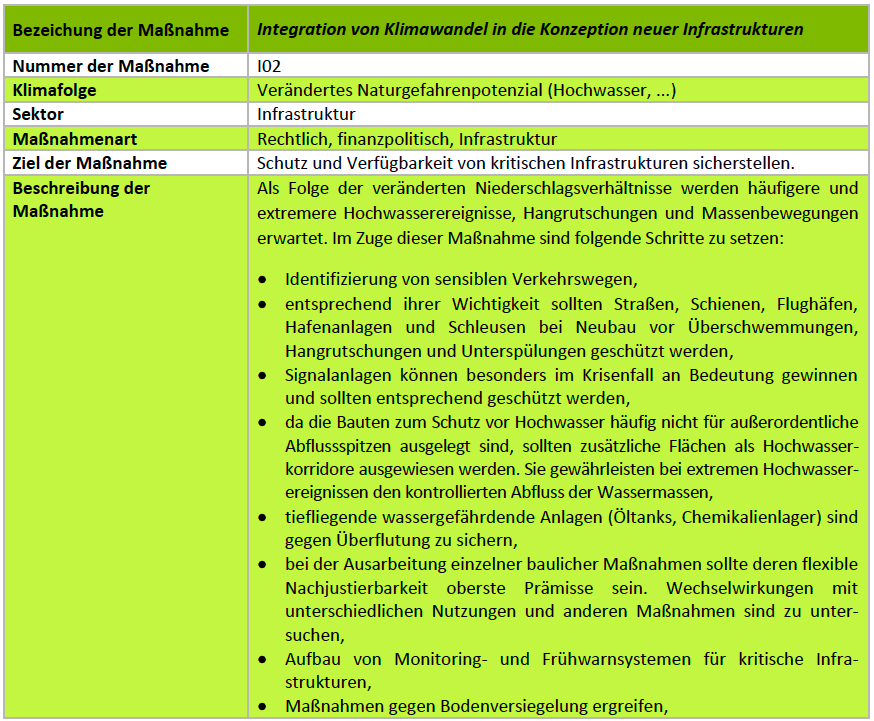

There are several measures for each topic and every measure is described in a factsheet. These detail the objective, the type of measure, necessary steps, additional information, stakeholders and success indicators.

With the detailed factsheets, the strategy also offers guidance and information on responsibilities. Municipalities can identify measures based on the desired effects of their actions.

Required resources

The resources used to create the strategy are not known.

Results

The strategy has been developed in a participative process, involving municipal and national planners. Recommendations respect the national and local planning regulations.

Every recommendation is explained in a table format (see below). It comes with a detailed description, ensuring that a measure follows the climate change adaptation strategy. Key stakeholders to implement recommendations are also detailed.

Despite the comprehensive guidance, measures still need to be translated into the local context by municipalities. This ensures that decisions respect local specificities. It also ensures municipal planning autonomy, a valuable commodity in the Grand Duchy.

The strategy has been adopted by the Luxembourg Government. All public institutions are asked to consider the document in the planning of public projects.

Experiences, success factors, risks

Adapting spatial planning to climate change is a difficult task. The strategy contains much useful information for planners and experts, helping to inspire national and local action.

Conclusions

The strategy is a reference document for climate change adaptation from 2018 to 2023. After 2023 it will be revised and updated again, to incorporate new knowledge and new planning legislation.

Contact

Contact: https://environnement.public.lu/fr/support/contact.html

References

Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Sustainable Development, Strategy and action plan for climate change adaptation: