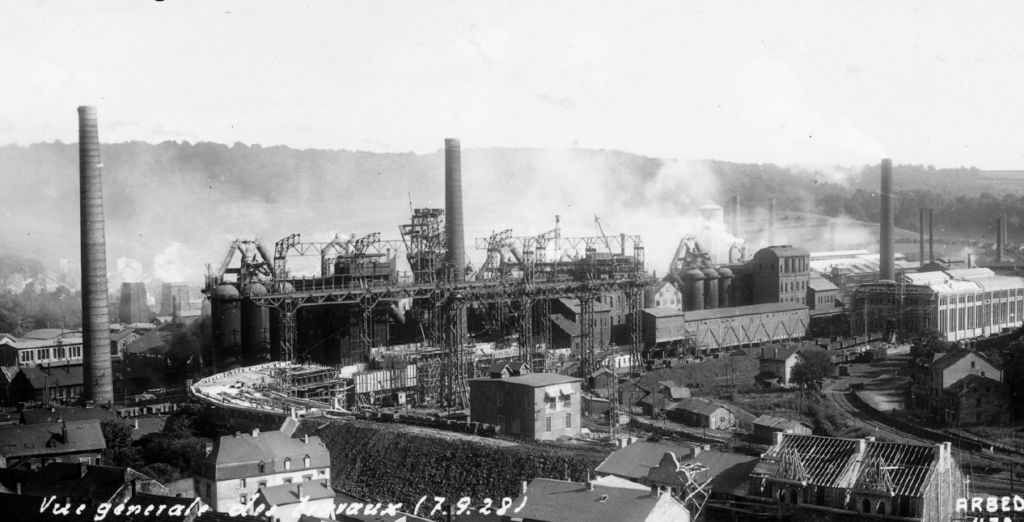

The south of Luxembourg is marked by the heritage of the steel industry and mining. Large active and inactive industrial sites next to urban centres remind residents and visitors of the peak of heavy industry. Located in the south of Dudelange city centre, the Schmelz district was home to a steel mill until 2005. The 40-hectare site is now undergoing a major brownfield reconversion project.

Rationale for action

Following the steel crisis in the 1970’s, more and more steel mills closed. Since then, the ongoing structural change has also affected Luxembourg’s south. In 2005, the former Schmelz steel mill was closed, which created a 40-hectare industrial brownfield site next to the city centre. The municipality saw the opportunity and kick-started a process to convert the site into a new urban district.

Objective

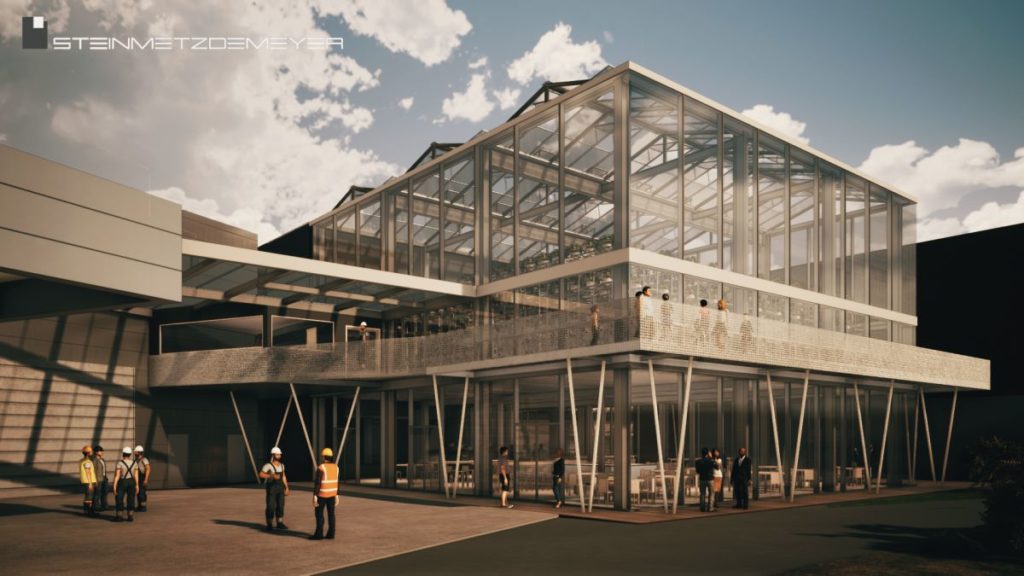

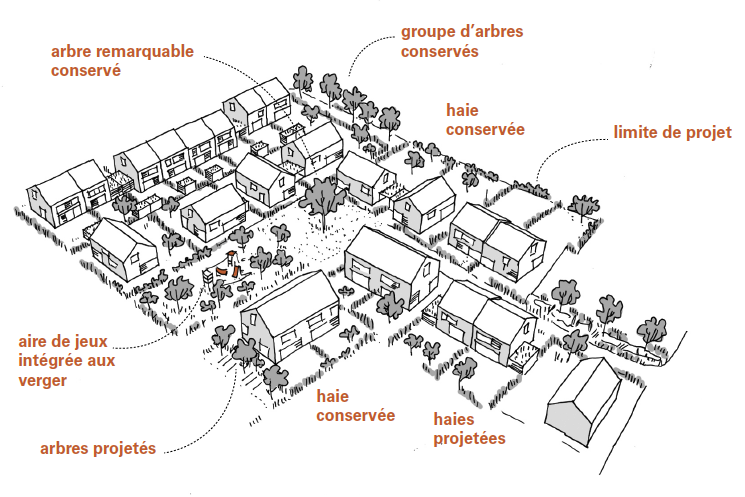

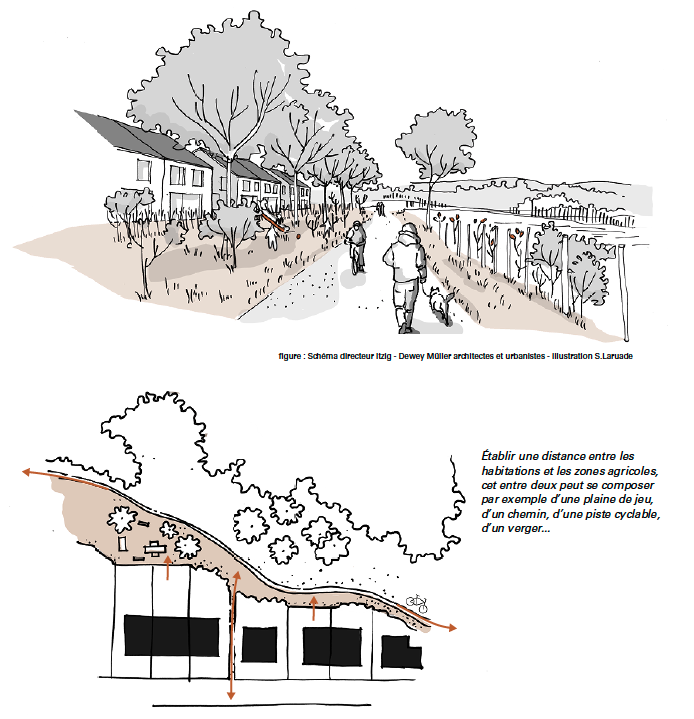

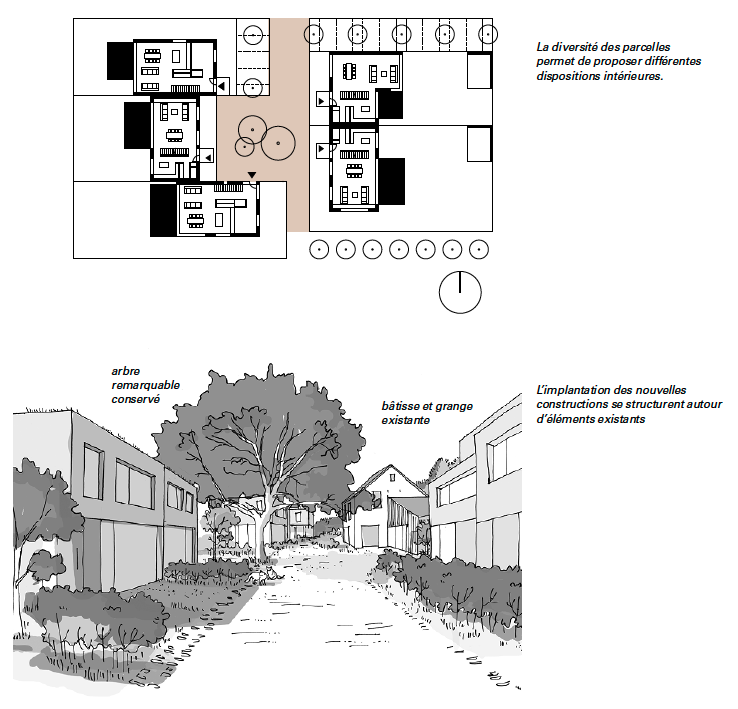

The central objective of the NeiSchmelz project is to construct a new district with housing, commercial and cultural areas connecting the districts of Italie and Schmelz to the city centre. Preserving the heritage of heavy industry is particularly important for the municipality. Therefore, the municipality intends to maintain the former industrial character, by preserving industrial artefacts such as the water tower and the floor plan of the factory buildings.

NeiSchmelz will offer approximately 1 000 new housing units. The new district should be multifunctional, mixed and attractive also for locals. By involving the Housing Fund (Fonds du Logement) in the development, housing will also be available for prices below market value, which will further promote a social mix.

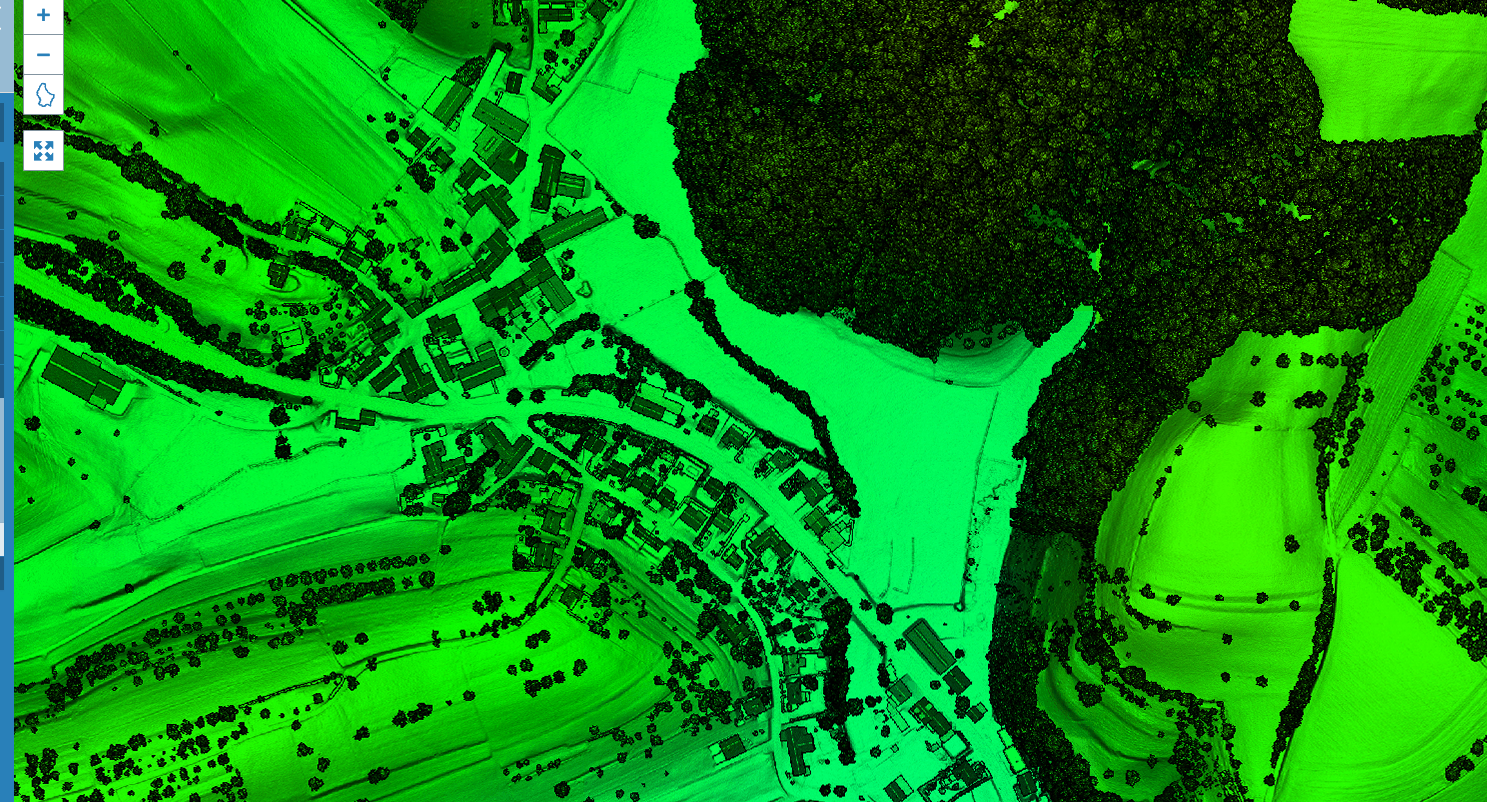

The new district will have easy access to Dudelange city centre, to surrounding districts, to green recreation areas and to the national traffic infrastructure. In addition to existing railway lines for example, there will be new traffic infrastructure within the new district and towards the surrounding areas (pathways, bike lanes, roads).

Time frame

The development started in 2008 and is ongoing (2021). The participatory phase started back in 2009 and the interim use concept was developed in 2011. A decontamination study and negotiations between the steel company (Arcelor Mittal) and the state were finalised in 2016. Since then, urbanistic concepts are being developed and implemented.

Key players

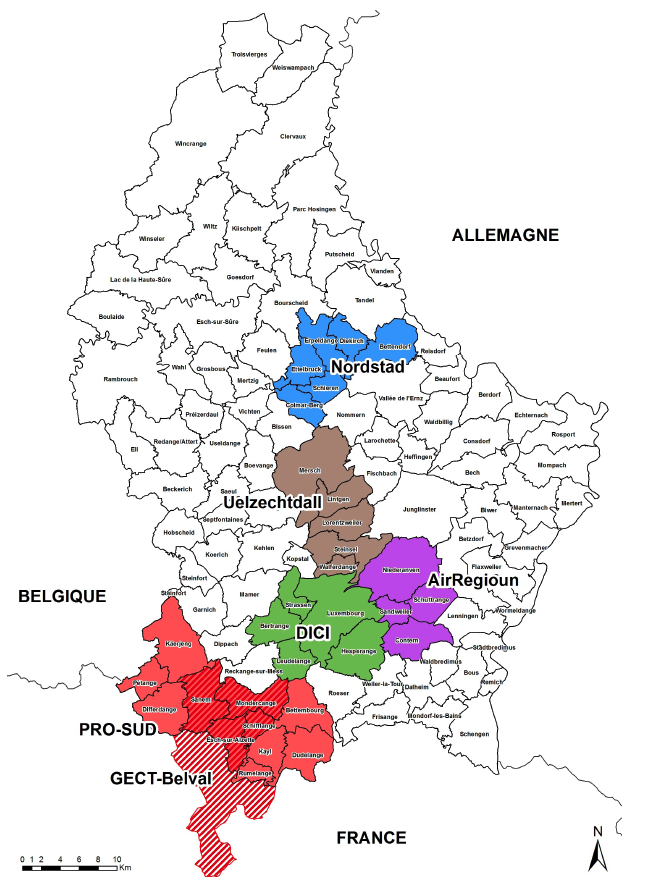

City of Dudelange, Housing Fund (Fonds du Logement), Luxembourg state functions (environment and water management administration, public roads and bridges administration (all under the Ministry of sustainable development and Infrastructure), CFL (national railway company)), Luxembourg EcoInnovation Cluster, developers, architects, civil society (community and social enterprises) and private developers.

Implementation steps and processes

After the former steel mill closed in 2005, the municipal administration issued a call for proposals in 2006 to gather ideas for future use of the site. In 2008, there was a decision to create a new urban district with a focus on housing. A national call for development proposals was launched in 2009. In 2010, the NeiSchmelz proposal was awarded and planners were contracted to develop the master plan for the district. In parallel, a concept to decontaminate the area was elaborated. In the meantime, an interim use concept was initiated and the master plan was finalised in 2012. Negotiations between the steel company, who owned the site, and the state finished in 2016, transferring ownership of the site to the state-owned Housing Fund.

Alongside implementation, a participatory process involving the public was organised. From 2009 to 2016, local residents and interest groups could incorporate their ideas for the interim use and final state of the conversion. This was achieved through information campaigns, multiple consultations and workshops. Presentations of the project highlight changes introduced through the public consultation procedure to illustrate to citizens how their contribution has influenced the project.

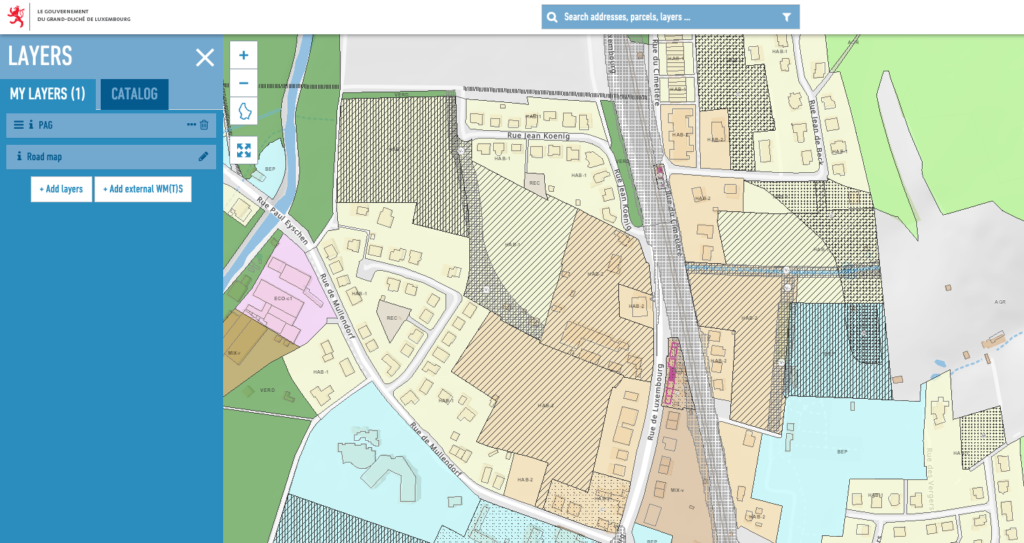

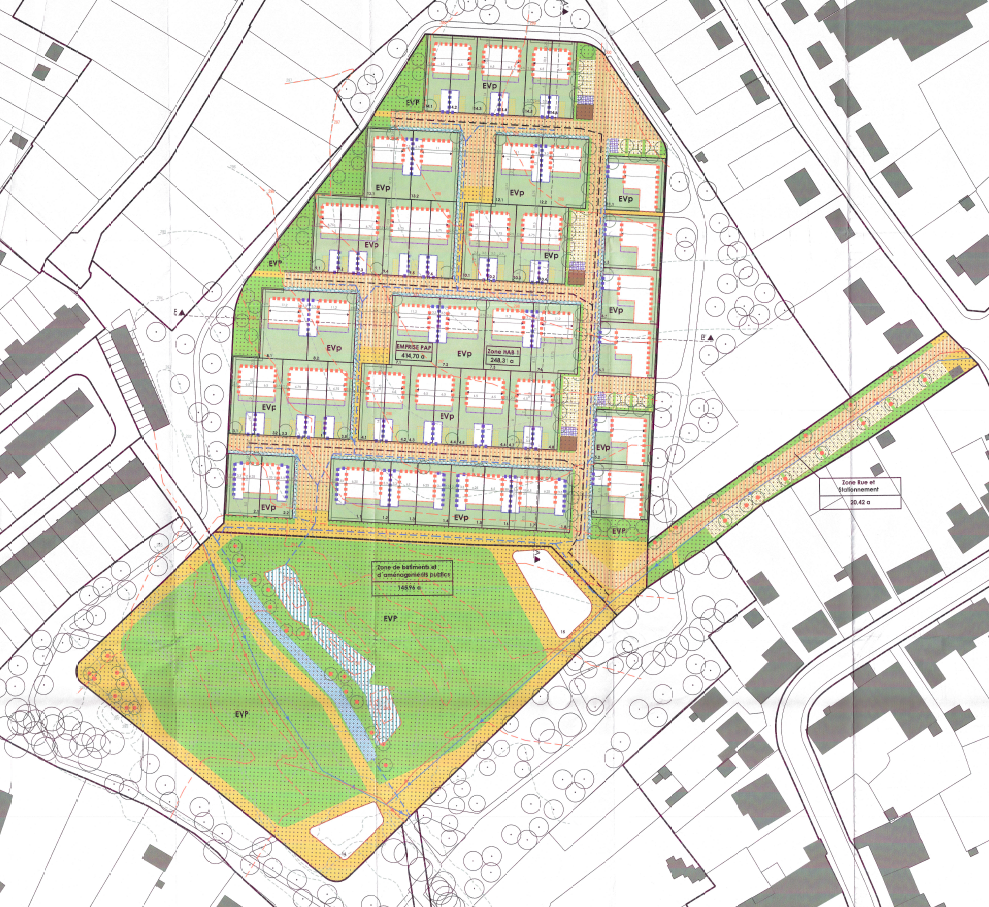

In order to develop the site, the municipal land-use plan (PAG) had to be changed. For the technical implementation, the city will rely on four so-called PAP (partial land-use plans). These act as building permits and were submitted for approval in late 2017.

Required resources

Since the project is implemented stepwise, the required resources cannot be specified. A key aspect for the project, however, was the acquisition of the site from the steel company.

Results

So far, there are few results of the conversion project. 1 000 new housing units will create living space for around 2 000 new residents. Additionally, there will be new commercial areas as well as public and semi-public areas for social and cultural exchange. A large area in the centre of the district will be for businesses, targeting start-ups and innovative enterprises. Building permits, in the form of partial land use plans for the new district were submitted for approval in late 2017 and approved in 2019.

Experiences, success factors, risks

Reconversion provides the opportunity to bring new types of land use into an urban area. NeiSchmelz creates a new residential district with businesses and public spaces. At the same time, the project illustrates how cultural heritage from the steel industry can be preserved while changing the usage of the site.

This industrial reconversion is a large-scale project that benefits from multi-level governance arrangements. In particular for the negotiations with the globally acting industrial companies, it was important to involve a national player.

The project is similar in size to other conversion projects in Luxembourg. For most of these projects, the sheer size in relation to the immediate surroundings and existing urban fabric poses special challenges for planners and architects.

Conclusions

NeiSchmelz illustrates that participatory processes, if implemented thoughtfully, have an impact on the length of a planning process. Participation, however, is key to acceptance of the new project and should thus represent a central pillar in the planning process. A good project requires effort and time.

Contacts

Ms Eva Gottschalk, Chief planner of the City of Dudelange: Eva.Gottschalk@dudelange.lu

References

City of Dudelange, 2021: project website: http://www.dudelange.lu/fr/projets-urbains/projet-neischmelz

City of Dudelange, 2013: participation report: http://www.dudelange.lu/fr/Documents/2013_Neischmelz-Rapport.pdf